The 2024 Senate map is conventionally challenging for Democrats. Republicans need just two seats to flip the chamber, while Democrats must defend 23. Eight of the states that they are defending were more Republican than the nation in 2020 and three (Montana, West Virginia, and Ohio) backed President Trump twice while voting more than ten points to the right of the nation in both 2016 and 2020.

But Democrats haven’t always struggled with the Class 1 map in presidential years. In 2012, Democrats coasted to a strong 55-seat majority by winning four high-profile Senate contests in state won by Republican Mitt Romney. Senate Democrats also netted seats on this map in 1988 and 2000.

Since President Obama’s reelection, however, many formerly swingy Democratic states have lurched to the right, causing ticket-splitting to evaporate. That’s why Republicans should be ostensible favorites to retake control of the chamber following the 2024 presidential election. But there are some problems with that assumption.

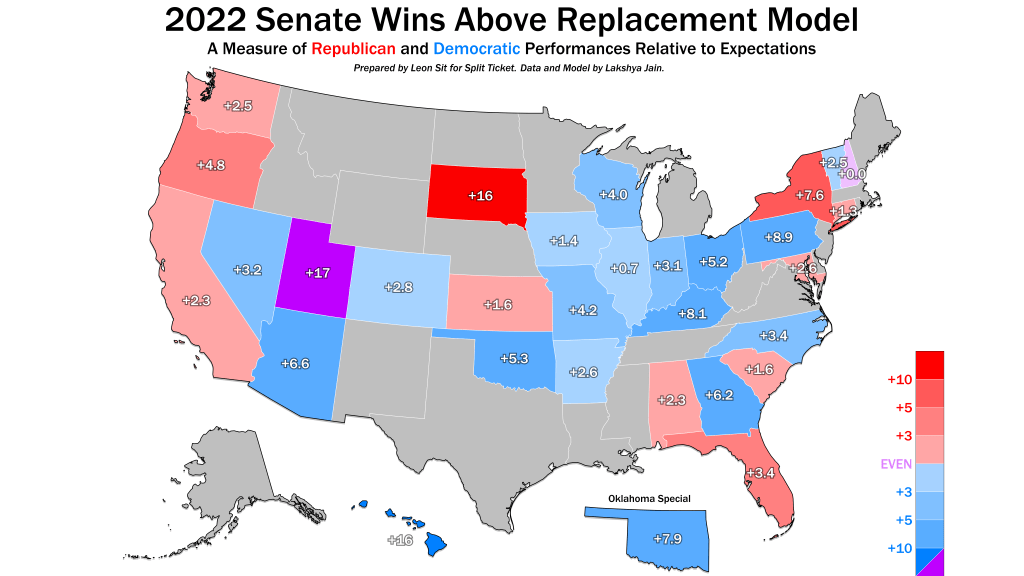

Republicans have repeatedly struggled to nominate high-quality candidates in important Senate races. Former President Donald Trump’s pull has only exacerbated the GOP’s candidate quality woes. In fact, we can quantify the harm this has done to the Republican Party’s overall majority using our Wins Above Replacement models, which allow us to estimate candidate strength after putting in controls for fundraising, incumbency, demographics, and state partisan lean.

Our estimates suggest that in the post-2016 era, Democrats have won ten extra Senate seats due to candidate quality, while the Republicans have won just two. Even though the GOP took back the seat they lost to Doug Jones in Alabama in 2020, our estimates suggest that questionable Republican candidates have cost the GOP a net seven seats — the current Senate has 51 Democrats and 49 Republicans, but under a slate of 100 generic matchups over the last three cycles, we would have expected a 56R-44D chamber. The US Senate has an R+4 chamber bias, on average (the 50th seat is roughly 4 points right of the nation), but the candidate quality differential has virtually neutralized it thus far.

While this issue has existed for some time (Christine O’Donnell, Ken Buck, Todd Akin, and Richard Mourdock come to mind), it is a problem that appears to have gotten worse of late and has accelerated with the emergence of Donald Trump, whose handpicked nominees generally underperformed massively across the board. In fact, 2022 saw the worst-performing Senate GOP field in recent memory, with Blake Masters, Mehmet Oz, Herschel Walker, and Adam Laxalt all losing races against strong Democratic nominees due to a wide gap in candidate quality.

We have discussed 2022 in great detail already, and you can find our postmortems on that cycle here and here. A better question may be whether Republican candidates would avoid underperformances this severe in presidential cycles. In fact, a popular argument in conservative circles in the wake of the unexpectedly close 2022 elections holds that Donald Trump’s singular presence on the ballot provided a huge boost to candidates by turning out extra Republican voters, and that 2024 would see a larger differential turnout advantage among Republicans.

We are more skeptical of this theory. The boost in turnout, if it exists, probably would not be strong enough to outweigh the drag on the overall topline that would be caused by independent and persuadable voters’ aversion to Trump. In fact, Democrats actually won independents in 2022, gained a Senate seat, and likely only lost the House because of weak Democratic turnout.

The path to Republicans winning the White House and Congress in 2024 lies in winning back independents who opposed the party in any of the last three election cycles. Republicans can best achieve this by nominating high-quality, mainstream candidates — regardless of the national environment. While ticket splitting hit record lows in 2020, Republicans were not fully insulated from the candidate quality issue in that cycle, either.

In 2020, Democrats flipped Arizona, Colorado, and both Georgia seats while losing Alabama. Our estimation is that three of those seats (Arizona and both Georgia seats) were won on the backs of large candidate quality differentials, with Jon Ossoff, Mark Kelly, and Raphael Warnock putting up WAR scores of D+6, D+4, and D+4 against David Perdue, Martha McSally, and Kelly Loeffler, respectively. This issue was largely one-sided, too — only one Republican won a seat that a generic nominee would have lost, and it was Maine Senator Susan Collins, a prominent member of her party’s centrist wing.

While it is fair to say that Republicans have nominated weak candidates more often as of late, it’s important to remember that Democrats have picked strong contenders too. The battleground Democratic incumbents of the Class 1 Senate cohort all fit this category. In other words, Republicans have an excellent chance at winning back the majority in 2024, but need to unseat formidable incumbents in to do so. To gain a better sense of just how electorally strong Class 1 really is, it makes sense to look at 2018 WAR.

In the 2018 cycle, Republicans lost three seats that should have been layups under ordinary circumstances. Just like 2022, lower-quality nominees reduced Republican chances — GOP candidates Patrick Morrisey and Matt Rosendale both had loose connections to their respective states (West Virginia and Montana) and underperformed exceptionally against strong Democratic incumbents Joe Manchin and Jon Tester. The candidate quality delta disadvantaged Republicans even more in Alabama’s 2017 Senate special election, where accused pedophile Roy Moore narrowly lost to Democratic prosecutor Doug Jones.

Those three disappointments were tempered by Republican pick-ups in North Dakota, Missouri, Indiana, and Florida, the last of which could be attributed to popular Governor Rick Scott’s handling of Hurricane Michael. The flips helped them compensate for losses in Arizona, where now-Independent Kyrsten Sinema beat Martha McSally, and Nevada, where Dean Heller’s spirited fight was not enough to fend off Jacky Rosen’s strong challenge. But Republicans still lost a net of two more seats than expected in 2018. That performance exceeded their 2020 and 2022 ones, but may not be enough to cut it in 2024.

In the coming cycle, Republicans will play for the seats in Nevada, Arizona, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Montana, and West Virginia while defending incumbents in Texas and Florida. GOP candidates should be favored to hold on in the Lone Star and Sunshine States while gaining in ruby red West Virginia. But the strength of the Democratic field in the other swing states, combined with the GOP’s recent tendency to nominate weak candidates, makes us cautious to confidently discuss the Senate more than a year in advance.

If Republicans want to win Democratic seats in swing states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, or Wisconsin, then they must pick stronger challengers than those from the last three cycles, because incumbent Democrats with formidable electoral records, like Bob Casey, have lots of cash to defend themselves with. Nominating a weak challenger against Jon Tester (+11 WAR) could once again cost the GOP a chance at carrying R+16 Montana. Unseating incumbents like Bob Casey (+3 WAR) and Tammy Baldwin (+1 WAR), meanwhile, would require the GOP to put up stronger challengers in both states than it has in the past few cycles.

In Arizona, Sinema’s Independent candidacy may complicate the entire equation, but current polls show Democratic congressman Ruben Gallego (a consistent House overperformer with a 2022 WAR of +4) leading every theoretical matchup. In Michigan, candidates like Elissa Slotkin or Garlin Gilchrist — on part with retiring Democrat Debbie Stabenow — would likely be outright favored against all but the best Republican recruits (e.g., Peter Meijer or John James). Republicans may have an even harder time in a marginal Biden-won state like Nevada, where a GOP nominee like Adam Laxalt (-3 WAR) likely would not outrun the eventual Republican presidential nominee by enough to win, despite Rosen’s net-negative favorability and 2018 underperformance.

Nothing can be taken for granted in the political world, and this is especially true of elections. If the Republican Party nominates candidates that are on par with the ones they’ve put up in recent cycles, though, flipping the Senate could get harder in 2024 despite an ostensibly favorable Class 1 map. For now, the onus is on Republicans to nominate the high-quality candidates needed to extend the playing field beyond Ohio and Montana. Until then, observers may wonder whether candidate quality issues are really an anomaly in the current GOP.

—

If you’ve read this far, we wish to now offer a brief side note. For those of you familiar with our site, we have spent a lot of time quantifying elections and electoral performance. We believe that an objective, data-driven metric to assess candidate quality is a vital resource that is sorely lacking, and that it helps significantly when forecasting future elections — for example, understanding Mark Kelly and Raphael Warnock’s candidate-specific strengths helped us avoid picking Republicans to win both states in November. Today, we’re excited to announce the full launch of our site-wide candidate quality database, with the revamp of our 2018 and 2020 wins-above-replacement (WAR) models to accompany our existing 2022 one.

Many of you may remember the initial drafts of these models, made in early 2022. These models were quite simple (especially the Senate ones), but still gave us valuable insight. Since then, however, we have made several methodological and modeling advances that we debuted in our 2022 Wins Above Replacement pieces. These include the use of improved regression techniques, better ways to control for spending and demographics, and a significant revamp in the Senate modeling methodology — namely, we now also train our Senate model on the House dataset for a given cycle, which gives us a much more stable model for the upper chamber.

These improvements made our 2022 models significantly more well-calibrated, especially compared to our previous ones, and so we decided to apply them to our 2018 and 2020 models to improve their consistency and quality as well. The results are now significantly sounder and are also better-calibrated, and they are different enough from our previous iterations to where we felt that a re-launch was warranted.

The above plot shows how predictive our relaunched WAR metric has been across cycles. On the left, we see its predictive power between 2018 and 2020, where roughly 46% of a candidate’s strength carried over from the midterm to the presidential year. On the right, we see its predictive power between 2020 and 2022, where 55% of a candidate’s strength carried over. Generally speaking, we observe that on average, 50% of a candidate’s strength carries over across cycles, and the upward tilt of the axes suggests that the metric is quite valuable in predicting future overperformances and may add value to models.

We hope that we have added some value to the discourse about candidate quality, and that our new database helps those interested in U.S. elections to make data-oriented conclusions about important races and the validity of conventional wisdom in the forecasting world.

—

We hope you enjoyed this piece. If you did, please consider subscribing to get our articles in your inbox for free!

I’m a software engineer and a computer scientist (UC Berkeley class of 2019 BA, class of 2020 MS) who has an interest in machine learning, politics, and electoral data. I’m a partner at Split Ticket, handle our Senate races, and make many kinds of electoral models.

My name is Harrison Lavelle and I am a political analyst studying political science and international studies at the College of New Jersey. As a co-founder and partner at Split Ticket, I coordinate our House coverage. I write about a variety of electoral topics and produce political maps. Besides elections, my hobbies include music, history, language, aviation, and fitness.

Contact me at @HWLavelleMaps or harrisonwlavelle1@gmail.com

I make election maps! If you’re reading a Split Ticket article, then odds are you’ve seen one of them. I’m an engineering student at UCLA and electoral politics are a great way for me to exercise creativity away from schoolwork. I also run and love the outdoors!

You can contact me @politicsmaps on Twitter.

I’m a political analyst here at Split Ticket, where I handle the coverage of our Senate races. I graduated from Yale in 2021 with a degree in Statistics and Data Science. I’m interested in finance, education, and electoral data – and make plenty of models and maps in my free time.