Because American politics is dominated by a two-party system composed of Democrats and Republicans, it’s hardly a surprise that observers tend to neglect Libertarian candidates. After all, minor-party contenders usually raise little money and win very few votes, causing them to have insignificant impacts on general election outcomes.

Sometimes, however, Republicans do blame Libertarians for “spoiling” key races. More recently, a great deal of effort has been exerted by Republicans to keep Libertarians off the ballot, with efforts in Texas and Montana grabbing the headlines. Prior Split Ticket analysis finds some truth in these accusations, but it would be wrong to assume that Libertarians draw uniformly from Republicans. While the party’s coalition likely is more conservative on the whole, it is worth studying in greater depth.

Using exit poll data, we quantified the effect that formidable Libertarian candidates have had on statewide elections since 2008. Our findings are consistent across differing environments and in three separate states, suggesting that Libertarian-curious voters averse to the two major American parties share common, consistent characteristics.

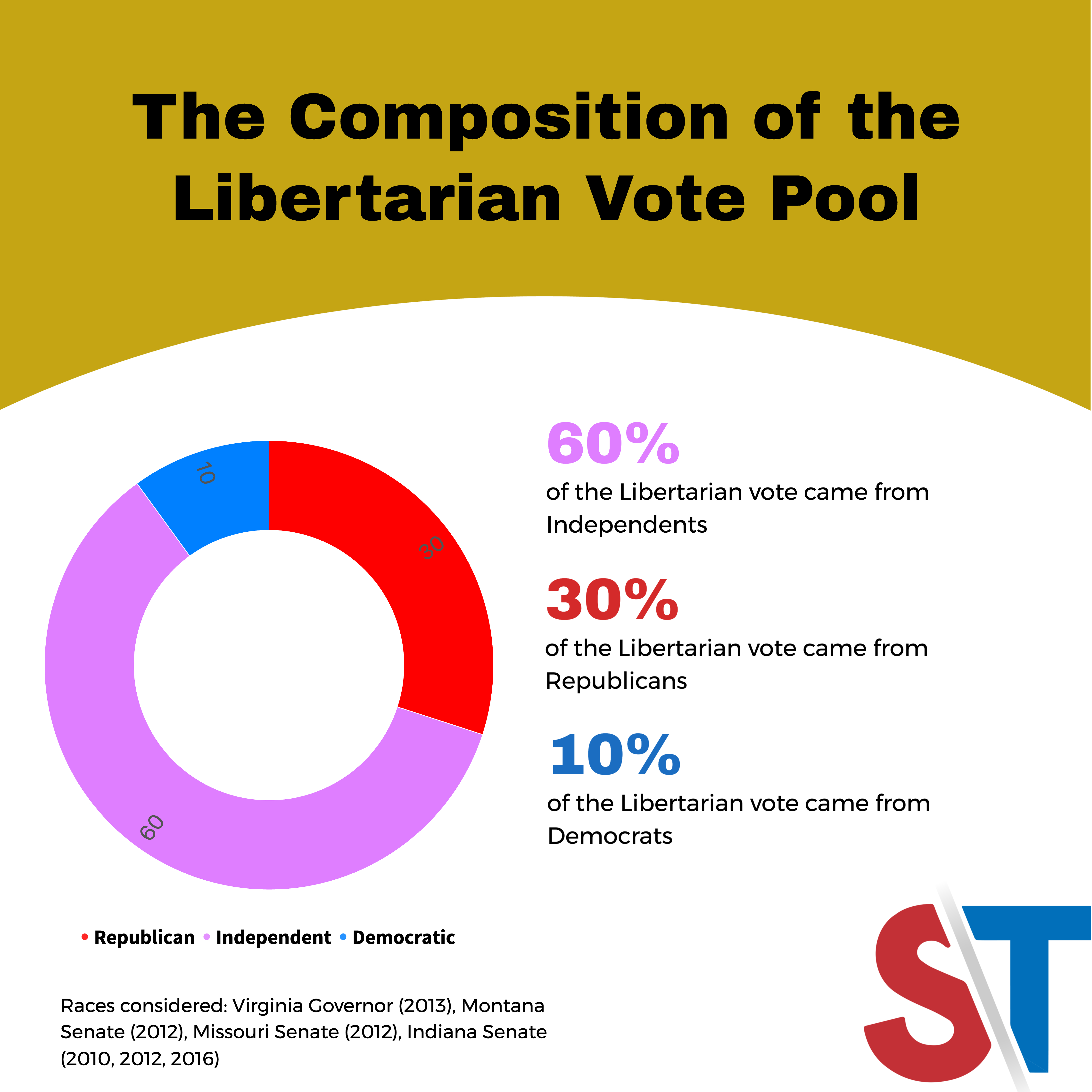

To examine what the traditional Libertarian pool of votes looked like, we took the Senate and Gubernatorial races between 2012 and 2020 that had a significant Libertarian vote share (at least 5%) despite both Republicans and Democrats fielding candidates. We then examined the Edison exit poll microdata, provided by the Roper Center, for each race that it was available for.

We stress that the findings below should be taken with an appropriate dose of caution, given the small sample sizes involved, and the possibility of individual, state-level effects. Nevertheless, we do find our research to be revealing in a few aspects where common threads appear, namely regarding the types of voters Libertarians tend to appeal to.

In the subset of races considered, 60% of the votes cast for Libertarian candidates came from Independents, with 30% coming from Republicans and 10% from Democrats. These types of gaps are robust enough to withstand the wide error bounds that would accompany any exit poll analysis, and they indicate that the Libertarian candidates in the considered subset drew primarily from self-identified Independents.

This is not surprising when we consider the nature of these voters. While they may have their own ideological slants, they are still the least partisan and least engaged group overall. For an example of how disengaged self-identified independent voters can be, it may be worth revisiting this chart we made from a Marquette University poll a while back, showing how the majority of “true independents” could not name a single sitting Supreme Court Justice.

These voters are not as attached to the two-party system and are not as politically aware as committed partisans are. Perhaps relatedly, they also happen to be the group that is friendliest to the Libertarian Party. While the partisan composition of Libertarian coalitions suggests that their voters are indeed more conservative than not, the breakdown of voter engagement by self-identified affiliation suggests that they are generally not the same as Republican partisans and should not be treated as such.

Who Have Libertarians Taken Votes From?

Another way of analyzing Libertarian coalitions is to see the rates at which each party’s voters voted for the Libertarian candidate. For this, we considered the aforementioned Senate elections, plus Donald Rainwater’s third-party gubernatorial bid (for which we got data from AP Votecast).

Self-identified independents were the most receptive to Libertarian candidates — analysis of Edison exits suggested that the party pulled 12% from this group in the average case. Among the two major parties, 5% of Republicans tended to vote for a Libertarian, while only 2% of Democrats voted for one, though we stress that this gap may be magnified by state-level variance and some massive candidate quality issues faced by Republicans in these races.

It may be worth examining what these findings indicate about the Libertarian Party’s overall coalition. Its voters are generally more conservative-leaning, but the degree to which this is true depends on the split of the independents. If we considered an electorate that was evenly split between the three groups and then used the statistics above to assume that 5% of Republicans and 2% of Democrats voted for the Libertarian, then the group would clock in at roughly R +40 overall among partisans. However, splitting independents (the largest Libertarian-voting bloc) straight down the middle would point towards an electorate closer to R+17.

These estimates align decently with analysis of the 2000 and 2004 elections done by the Cato Institute. We can also check the Cast Vote Record in counties that provide it to augment our analysis. One such county is heavily white, Trump +24 Glynn County in Georgia. Here, according to Jesse Richardson, voters that backed Libertarian Chase Oliver instead of Herschel Walker or Raphael Warnock in the 2022 Senate race also backed Brian Kemp by 60 points, suggesting that Oliver drew most of his support from conservative-leaning voters who couldn’t stomach Herschel Walker. But in 2020, Republican David Perdue won Libertarian Presidential candidate Jo Jorgenson’s voters by only 21 points in the two-way vote, which was actually left of the county overall. This further indicates that the Libertarian coalition, while generally more Republican than not, is subject to massive variance based on the major party candidates running.

The purpose of this piece is not to determine the exact partisanship of Libertarians. That varies by state, and any estimates will almost certainly have large error bounds around them. The main takeaway is simply that these voters, while historically Republican-leaning overall, are meaningfully very different from Republicans, and that their pull is strongest with ostensibly Republican-leaning independents. Our research also suggests that the Libertarian has functioned differently in different races; often, they serve as a “protest” mechanism for many people dissatisfied with their party’s candidates, meaning that when a candidate garners significant blowback, defections hasten disproportionately from their party.

An excellent example of this phenomena is in the performance of Donald Rainwater, the best-performing Libertarian candidate in our sample. Rainwater took 11% of the vote in Indiana’s 2020 gubernatorial election, finishing ahead of poorly-funded Democratic nominee Woody Myers in several deep-red counties and winning 15% of self-identified Republicans.

Given that Rainwater’s Republican opponent Eric Holcomb was an incumbent governor unpopular among right-wing voters for his coronavirus mitigation policies, it’s fair to say that the Libertarians benefited from conservative defections. Other strong Libertarian candidates like Andy Horning and Jonathan Dine, meanwhile, likely did well thanks to conservative-leaning voters who found controversial Republican Senate nominees Richard Mourdock and Todd Akin unacceptable.

Current Implications

Should Republicans continue to struggle with candidate quality in key Senate races, formidable Libertarians may become acceptable alternatives for soft conservative voters. Assuming the Democratic challenger does not win outright, strong Libertarians tend to hurt weak GOP candidates — especially those in red states.

Nowhere is the importance of a credible Libertarian candidate expected to be more important in 2024 than in Montana, where Democratic Senator Jon Tester is fighting against his state’s Republican lean to win a fourth term. Of Tester’s three elections, prior Split Ticket research suggests that only one could have possibly been caused by a Libertarian spoiler: his initial 2006 victory against sitting Republican Conrad Burns. Even then, Burns’ projected reallocation margin was within the margin of error and 538 turnout analysis suggests that about 90% of Libertarian voters would have had to vote in a two-party race — a fairly high sum given historic attrition estimates. Tester’s more recent wins were not at all attributable to any Libertarian, and he even won a majority of the vote against Matt Rosendale in 2018.

In spite of his prior successes, his upcoming reelection is widely expected to be his most difficult because polarization is much more pronounced now than it was in 2012, the last presidential cycle Tester was reelected in. Having a credible Libertarian candidate on the ballot drawing votes away from persuadable Republicans and conservative independents would therefore work to Tester’s advantage — possibly helping him win with a plurality in this Trump +16 state.

The potential impact of a formidable Libertarian is compounded by the fact that Republicans could end up nominating a weak candidate. Congressmen Matt Rosendale and Ryan Zinke, two of the most prominent candidates considering challenging Tester, are both wins-above-replacement (WAR) underperformers.

In an attempt to bypass the historical “spoiler effect” caused by Libertarian candidates, Montana’s Republican state legislature tried to get a new bill signed into law that would make the 2024 Senate race a top-two election between Tester and any Republican. This legislation was recently shelved, but even if it were to become law, historical evidence suggests that it wouldn’t kill Tester’s odds of victory.

While the bulk of the evidence suggests Libertarians are more GOP-friendly than not, the data suggests that their pull is actually strongest with independents, from whom they draw a majority of their vote. And while the Libertarian Party historically has drawn more votes from Republicans than from Democrats, the historical composition of their coalition suggests that many of their voters would likely have voted for the Democratic candidate or skipped the race entirely if a credible third-party candidate were not on the ballot. As social issues such as abortion come to eclipse fiscal issues for many voters, it’s not hard to imagine the libertarian-minded among them voting with their conscience rather than with their wallet.

Regardless, one thing appears to be clear: it is a mistake to simply treat all Libertarian voters as de-facto Republicans. Because if they were, they probably would have just voted for the Republican.

I’m a software engineer and a computer scientist (UC Berkeley class of 2019 BA, class of 2020 MS) who has an interest in machine learning, politics, and electoral data. I’m a partner at Split Ticket, handle our Senate races, and make many kinds of electoral models.

My name is Harrison Lavelle and I am a political analyst studying political science and international studies at the College of New Jersey. As a co-founder and partner at Split Ticket, I coordinate our House coverage. I write about a variety of electoral topics and produce political maps. Besides elections, my hobbies include music, history, language, aviation, and fitness.

Contact me at @HWLavelleMaps or harrisonwlavelle1@gmail.com