The Crossover Kings: Don Bacon and Jared Golden

Introduction

Crossover seats are districts that elect a Congressperson of a different party than their Presidential preference. Split-ticket voting is the stimulant behind these outcomes, so it makes sense that the increasing dominance of straight-ticket voting on the American political scene has reduced the number of districts yielding partisan splits.

In 2016, there were 35 crossover seats. 23 districts voted for Hillary Clinton and a House Republican; 12 backed Donald Trump and a House Democrat. Of the 23 Republican-held Clinton seats, 21 flipped to the Democrats as the party swept the nation to take the House in 2018. Two open Democratic-held Trump districts in Minnesota broke for the Republicans in that same year.

Just four years later, the number of crossover seats was halved to 16. Nine districts voted for Joe Biden and a House Republican; seven backed Donald Trump and a House Democrat. The implication was clear: crossover seats are becoming fewer and far between.

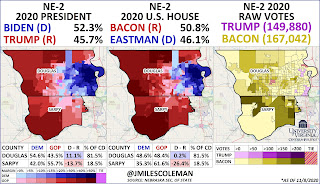

My piece on Friday will touch on more of these seats in some level of detail, but today’s article is devoted solely to Nebraska-2 and Maine-2. Last year, both displayed some old-school ticket-splitting. The two are also unique because they account for single electoral votes in Presidential elections. DEMs carried NE-02 in 2008 and 2020; REPs won ME-02 in 2016 and 2020. Crossover kings Don Bacon (R-NE02) and Jared Golden (D-ME02) both reaped the benefits of their appealing brands at the ballot box last year.

Thank you to Miles and Armin for the wonderful maps contained in this article!

Nebraska-2 (R – Don Bacon)

Nebraska’s 2nd district is based around Omaha, the state’s largest city. Under its current lines, the seat encompasses all of Democratic-leaning Douglas county and part of Republican Sarpy county. The Douglas portion accounts for 82% of the seat, though its redder suburbs are usually outvoted by the reliably-Democratic Omaha metro. To win, a Republican must keep Douglas close while dominating in southern Sarpy. The 2nd has more or less kept its current design since the 1992 redistricting cycle, when it shrank significantly in size.

For almost two decades, the 2nd was represented by Republican Lee Terry. Elected to the open seat in 1998, Terry was electorally reliable at first. He outran Bush twice and managed to hold on by four while Obama carried the district by a single point in 2008. But the 2012 cycle proved inauspicious for Terry, who ran behind Romney to eke out a close win in an otherwise favorable seat. Sensing vulnerability, the Democrats made sure to target him profusely in 2014.

After surviving a closer-than-expected primary challenge from his right, Terry faced off against Democrat Brad Ashford. The state Senator jumped into the race after top-Democratic recruit Pete Festersen ended his campaign. Democrats hit Terry for eschewing the

idea of refusing his pay-check during the 2013 government shutdown, leading Ashford to a somewhat comfortable victory on election day. Terry was one of just two Republican incumbents to lose their seats in what was otherwise a red year.

In 2016, Republicans hoped to bring the seat back into the fold post-Terry. They found their standard-bearer in Don Bacon, a retired Brigadier General utilizing the clever slogan “everybody loves bacon”. Ashford fought hard for a second term, but ultimately lost a close race. Trump carried the seat, but Bacon received a higher share of the vote than him.

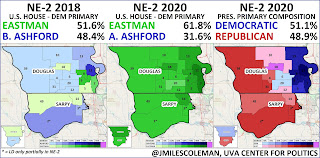

Ashford ran again in 2018 but lost the primary to progressive candidate Kara Eastman. Democrats thought they could ride a strong national wave to unseat Bacon, but the incumbent managed to hold on while increasing his margin from 2016. Eastman ran again in 2020, easily beating Ashford’s wife Ann in the Democratic primary to set the stage for November.

General election polling showed a heated contest, with the advantage bouncing back and forth like a hot potato. Eastman’s campaign got more attention the second time around due in large part to the Biden Campaign’s earnest desire to win the 2nd district. Bacon hadn’t yet had the chance to outrun the top of the ticket, so many Democrats assumed that Biden would pull his retread challenger over the line. They were sorely mistaken. Even those who expected Bacon to eke out a third term were probably surprised by the scale of his win.

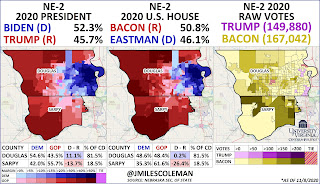

Biden carried the 2nd by almost 7 points, yet Bacon cruised to reelection by 5. That’s a staggering difference of 11! Bacon received 50.8% of the vote districtwide, a full 5% more than President Trump. Eastman trailed the former Vice President by 6% when it came to vote share – taking just 46%. The incumbent outpolled the President by a raw vote margin of 17,162 out of over 300,000 cast, putting him near Biden’s 176,468 vote tally. Let’s break down the results further.

In crucial Douglas county, accounting for 82% of the district, Bacon nearly won. He trimmed the Democratic margin to 0.2, down from 3 points two years prior. Biden carried the county by 11, leaving Eastman in the dust. The GOP stronghold of Sarpy delivered Bacon victory while padding his lead; he won by 26, nearly double Trump’s 14 point margin. Trump only received more raw votes than Bacon in the most minority-heavy segments of the Omaha metro.

What’s in store for the new 2nd? Under the recently-adopted lines, the Biden +6.3 seat gets just a tad redder. It is currently the only competitive district in the Cornhusker State, though Jeff Fortenberry’s 1st is now more favorable for Democrats at Trump +11. The new map’s weirdest feature is probably the addition of ruby red Saunders county into the western part of Bacon’s seat. Otherwise, the district is relatively unchanged. Given the similar partisanship, Bacon should have no issue holding his new seat in a Republican environment coupled with midterm turnout.

Maine-2 (D – Jared Golden)

Represented at one point by prominent Maine politicos Olympia Snowe and John Baldacci, the 2nd was more recently held by conservative Mike Michaud – the only type of Democrat that can win the district. A fairly popular incumbent, Michaud never faced much difficulty when it came to reelection. He retired in 2014 to run for Governor, but ended up with an embarrassing loss to his Republican foe Paul LePage. Former State Treasurer Bruce Poliquin won a fractious general election that year, flipping the seat to the GOP for the first time in decades.

Democrats had hope that state Senator Emily Cain would win her 2016 rematch, but Poliquin instead romped to a 9 point reelection. He took 55% of the vote as candidate Trump became the first Republican Presidential nominee to carry the 2nd’s single electoral vote,

while losing the state itself, since Maine began allocation by Congressional district

in 1972.

Outrunning Trump didn’t make him invincible, though. Maine’s new Ranked-Choice Voting system allowed state Representative Jared Golden to win the seat in 2018 after the first round of adjustments. Poliquin had initially finished ahead with a plurality of 46.3% of the vote, but ended up losing by a point after votes for lesser candidates

were redistributed. Golden was

the first House member to be chosen under an RCV system.

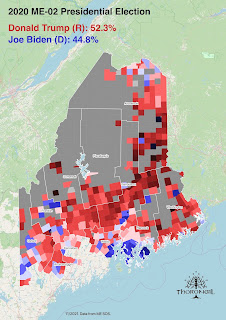

In 2020, Golden’s reelection chances were considered rock solid despite President Trump’s advantage in the 2nd district. He heavily-outspent his Republican opponent, former state Representative Dale Crafts. Golden did indeed have a comfortable victory, but his margin fell below pundit expectations. Talking head predictions aside, the freshman moderate did incredibly well given the President’s performance in his district.

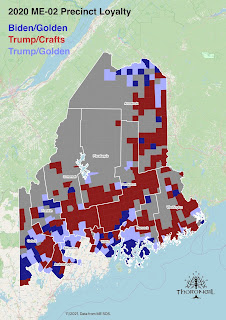

The third map is especially poignant because it shows the scale of crossover voting across the district. Municipalities in light blue voted for Trump and Golden, driving the difference in margin between the two contests. Golden ultimately won by six, taking 53% of the vote – about eight points higher than Biden’s. Trump carried the 2nd by 7.5 points, outpacing Crafts with 52% of the vote. Golden’s status as a Blue Dog Democrat has probably played a big part in boosting his appeal within his conservative seat.

After his closer-than-expected 2020 victory, Golden is seen as one of the top Republican targets ahead of next year’s midterm elections. His seat twice yielded an electoral vote for Trump, and his moderate brand may not be enough to save him next year if the environment is untenable. Nevertheless, he seems like he might be in a slightly better position than other Trump-district Democrats like Cindy Axne (IA-03) and Marcy Kaptur (OH-09). Former Congressman Poliquin is running again next year. The new 2nd is actually a bit bluer than its predecessor, though its overall design has been largely unchanged for the last few decades.

Crossover seats: What’s the future?

Considering the recent decline in split-ticket voting across the nation, the future of crossover seats seems rather bleak. While it’s impossible to predict the dynamics of the 2024 elections three years in advance without completed redistricting, we can still make educated guesses when it comes to the implications of general trends.

Assuming polarization continues its salient ascendance in American politics, voters will probably be less and less likely to vote for different parties on the same election night. In this America, the national environment’s omnipotence would lessen the importance of candidate quality, regional appeal, and individual strengths. As my colleague Lakshya has frequently pointed out: a state or district’s Presidential result is the most explanatory predictor of its downballot vote. If gridlock grows, topline margins should account for more and more of the variance in results between different offices elected on the same day (i.e. Senate or House).

We’ve already seen this phenomenon in play, and the aforementioned decline in the number of crossover House seats is not the only evidence of it. There has also been a noticeable decline in the number of states backing different parties for President and Senate when elections coincide. Six states did this in 2012; five voted for Romney and Democratic Senators and one voted for Obama and a Republican. Zero had split outcomes in 2016 and just one had a split result in 2020. In states backing the same party for both offices, the Presidential topline has even become predictive of vote share and downballot margin!

Split-ticket voting is certainly still a presence in gubernatorial elections, even in Presidential years. Democrat Jim Justice and Republican Phil Scott won close races in Trump +42 West Virginia and Clinton +26 Vermont in 2016. Scott and Chris Sununu (NH) were both reelected in Biden states last year. North Carolina Democrat Roy Cooper secured a second term even as the Tar Heel State broke for President Trump. Kentucky and Louisiana both have Democratic Governors; Maryland and Massachusetts both have Republican Governors. If anything, state-level contests are usually easier for the disadvantaged party to win because they are more disconnected from the divisiveness of national politics than their Senate counterparts.

That doesn’t mean split-ticket voting will evaporate forever, though. There will almost certainly be some crossover seats in 2024, but it wouldn’t be unreasonable to expect these districts to become increasingly akin to finding a four-leaf clover. Ahead of 2022, there are already a few Trump-district Democrats and Biden-district Republicans up for reelection; Bacon and Golden are two of them. Over the ensuing decade, the real question for political handicappers will be whether candidate appeal is enough to overcome the polarization of national tides.