“To be conservative as a young person means that one has no heart, but to be liberal as an old person means that one has no brain”.

The above quote is one of the oldest notions in politics, and it conveys the expectation that young voters, who consistently display the most liberal social attitudes, vote overwhelmingly for liberals at a young age before shifting to become far more conservative over the years. But an examination of young voters over the last five decades shows that the truth might be far more complex.

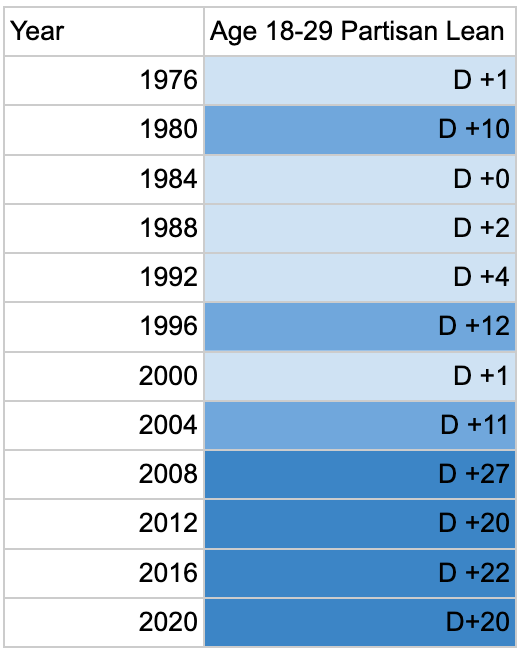

To begin with, data suggests that 2004 was really the beginning of the current period of age polarization in American politics. Before then, although it was not unprecedented for young voters to have elections in which they were significantly more Democratic than the nation as a whole, it was much more unusual — in five of the seven elections between 1976 and 2000, young voters were within five points of the nation’s partisanship overall. Since then, however, the gap has widened massively, and by 2020, young voters were twenty points more Democratic than the nation as a whole.

Why might this be the case? One good theory is ideological polarization — until recently, partisanship based on ideology was not nearly as prevalent of a phenomenon among voters. Conservative Democrats and Liberal Republicans are factions that held a significant amount of sway until the 2000s, but are virtually extinct today in their respective parties. In fact, a 2014 article from Pew Research suggested that in 1994, only 64% of Republicans were more conservative than the median Democrat. But 2014, this number had spiked to 92%, and has almost certainly only grown in the years since.

But is it true that voters get significantly more conservative as they age? This part is extremely unclear, but the general academic consensus points to this not being the case. Most academic research suggests that overall, political affiliations are actually quite stable over the long term, and that the notion that young voters will mostly become significantly more conservative over the long term is not really backed up by the data (though one study did find that while it was more uncommon than not, when shifts do happen, young liberals tend to become more conservative rather than the other way around). In other words, data suggests that while some shifts to the right may happen with time, there is no real reason to believe that the voters that voted for Obama, Clinton, and Biden by 20 points will become significantly more conservative relative to the nation as they age.

But there is another important component to this, and it is that of irregular voters. Young voters are some of the most irregular ones in the electorate, while older voters have consistently higher turnout rates. So is it possible, then, that the latent nonvoting pool of young adults may be more conservative on the whole? In essence, even if voters don’t become more conservative as they age, might it be true that with time, as engagement rates go up, more previously non-voting conservatives enter the electorate?

Perhaps. It’s quite difficult to track this, but one thing we can do is look at how exit polling suggests generations vote over the years. Essentially, we can look at how the youth vote went in every cycle between 1976 and 2008 and then see how that generation voted both twelve and twenty-four years later to see if the group actually became more Republican overall as it became a more regular and substantial part of the electorate. Before presenting the table, we should note two things: firstly, that the numbers below are normalized to be relative to the nation once again, and secondly, that the partisan leans twelve and twenty-four years later are Split Ticket’s best rough estimates of the groups based on exit polling and Catalist data. These should thus be treated with wide error bounds.

The average shift in twelve years is for a cohort to become five points more Republican, and the average shift in twenty-four years is for a cohort to become seven points more Republican. We must stress that exits are quite noisy, and so these estimates should be considered with the appropriate error bounds. But with this new lens and these new datapoints, it does seem that there is some truth to the notion that a generation votes more conservatively as it ages, though given the academic research on the matter, it might really be largely because more conservative voters that previously didn’t vote actually begin voting as they age.

But we want to point out something above in the table: young voters in 2020 were 20 points more Democratic than the nation as a whole, a margin that is comfortably greater than the average shift right, and one that could not be wiped out with even the largest 24-year shift in the table above. At the moment, Republicans currently rely on winning older voters in their coalition, having won seniors by an average of 6 points in the last decade, according to Catalist. But at some point, if they are unable to wipe out the Democratic advantage with Millennials and Generation Z, they will need to make serious gains among future young voters, because a party cannot continue losing young and old voters alike and expect to win elections.

We are not forecasting an emerging Democratic majority. Parties generally tend to adjust their coalitions and do what they need to in order to win. If, at some point, Republicans do get hit with a serious penalty for their weakness among today’s young voters (as we suspect they might), it is extremely likely that the party will shift stances in order to continue winning elections. Parties do not spend that long out in the wilderness, and the American public has historically been very averse to continuous one-party rule.

What we are saying, however, is that at some point, Republicans will probably have to reckon with the current deficit they face among the new generations, because the advantage of time is almost certainly not enough to wipe out a partisan gap that is bigger now than it was at any point before the Great Recession, and a party winning older voters by even a few points is a very, very powerful tool. In 2020, Catalist estimates suggest that voters under the age of 45 backed the Democratic Party by around 20 points, while voters over the age of 45 backed Republicans by a margin of 4. Even with an advantage that massive among young voters, Democrats only won nationally by a margin of 4.5 points, simply because voters over the age of 45 constitute a much, much bigger portion of the electorate (61%) than voters under the age of 45 do (their share is only 39%).

The generational gap between the two parties has recently grown to bigger proportions than ever before, and it is a historical anomaly for the gap to be this big for this long. Democrats have many red flags to watch out for in the electorate, including the acceleration of educational polarization making the Senate a very tough lift. But it would be irresponsible to pretend that only one party has any danger points for them in the long term, and at some point, as Millennial and Gen-Z voters begin to vote more regularly with age, the Republican Party will almost certainly have to figure out how to neutralize their overwhelming Democratic lean. Because history suggests that time probably is not going to be able to do this on its own.

I’m a software engineer and a computer scientist (UC Berkeley class of 2019 BA, class of 2020 MS) who has an interest in machine learning, politics, and electoral data. I’m a partner at Split Ticket, handle our Senate races, and make many kinds of electoral models.