Ahead of the 2026 midterm elections, Democrats are busy sizing up the weak points in the slim Republican majority to maximize their chances of taking back the House. And if history is any indicator, they have ample reason to be optimistic about their chances in the lower chamber. Whether it’s the “iron law” of midterm loss, the increased inefficiency of the Republican coalition, or thermostatic souring of public opinion on certain parts of the Trump agenda, the fundamentals are likely to work in their favor.

On top of that, polling is already bearing out the cyclical change in public opinion against the president’s party—a pattern that has defined virtually all recent midterm cycles. Since first overtaking Republicans in March, Democrats have extended their lead on the generic ballot to D+3; in the same timespan, President Trump’s approval rating has dropped to 9 points underwater.

To get a sense of which seats are in play for Democrats, we can use Split Ticket’s comprehensive WAR database. While it’s true that overperformances, especially large ones, have become much rarer during the Trump era, there are still a number of comparatively strong incumbents on both sides of the aisle. Key for both parties is the fact that incumbent strength plays an even more important role in midterm elections, when turnout is lower and less uniform—causing persuasion to matter more.

This is why Republicans in conventionally Democratic-leaning seats like Brian Fitzpatrick have been able to weather difficult environments before. At the same time, weak incumbents in conventionally Republican-leaning districts, like Scott Perry, have put their seats at greater risk of being lost.

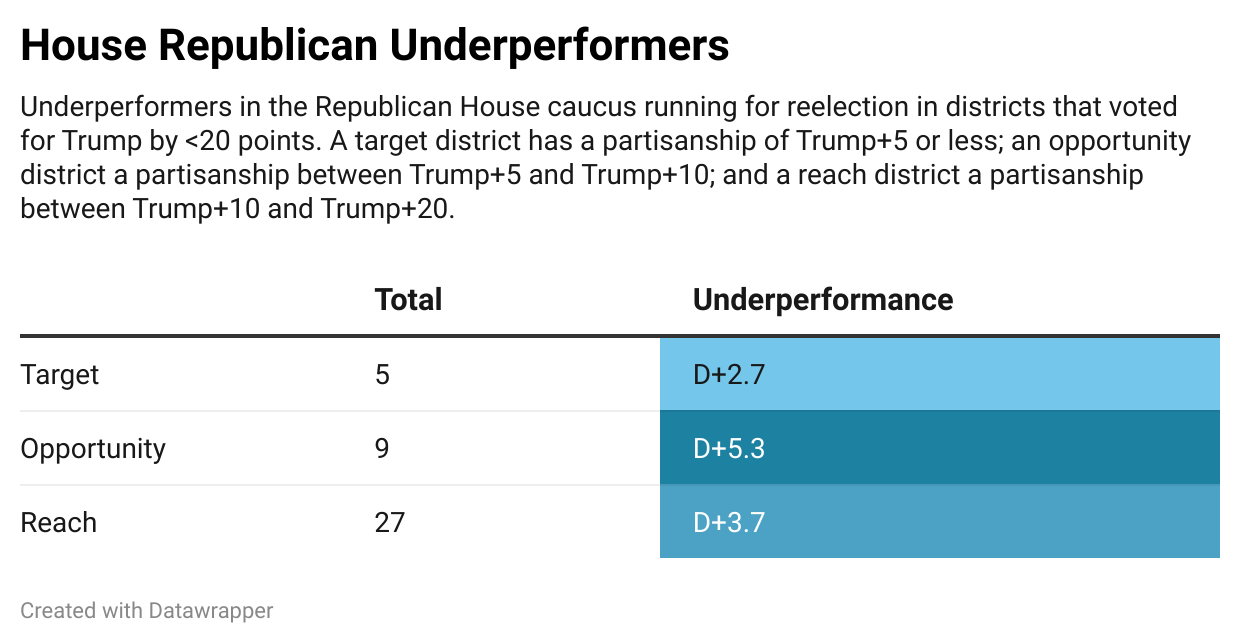

To map the 2026 Democratic playing field, we sorted the Republican caucus based on 2024 WAR score and then divided up the underperformers based on district partisanship. We define a target district as any seat with a 2024 partisanship of R+5 or less; an opportunity district as any seat with a partisanship between R+5 and R+10; and a reach district as any seat with a partisanship between R+10 and R+20.

We do not look at open seats, where retiring incumbents make the candidate quality landscape uncertain. Additionally, Republican incumbents who are running in 2026 but faced no Democratic challenger in 2024 are excluded.

Of the current Republican incumbents who underperformed last November, a total of 41 are running for reelection in districts that voted for Trump by 20 points or less: 5 in target seats (average underperformance of D+2.7); 9 in opportunity seats (average underperformance D+5.3); and 27 in reach seats (average underperformance D+3.7).

The bulk of the underperforming Republican members represent either reach seats or entirely uncompetitive districts. This distribution is not surprising considering the relative lack of swing districts and the gradual decline of crossover voting that has taken place over the last eight years.

It also supports the view that moderates are more electable, something we’ve written about extensively. A Republican like Lauren Boebert, for instance, may have been able to survive in her reach seat despite having a WAR score of D+9.2, but she wouldn’t have won in either an opportunity district or target district.

Other reach seat Republican underperformers who could see closer-than-expected races include Nick Begich (AK-AL), Eli Crane (AZ-02), Ryan Zinke (MT-01), Abe Hamadeh (AZ-08), Anna Paulina Luna (FL-13), and Monica De La Cruz (TX-15). Collectively, these members represent districts that voted for Trump by 14 points and have a WAR score of D+7.4—enough to give Democrats an outside chance.

When it comes to possible pickups, though, Democrats will be focusing on target and opportunity seats, which are inherently more competitive; already susceptible to flipping based on the environment alone, weak Republican incumbents could make the difference for Democratic challengers in these districts.

All five of the target seats held by Republican underperformers voted for Trump, but by less than 5 points in each case. The electorate in each of these seats is predominantly suburban, college-educated, and white. This voting bloc has consistently gotten more Democratic since 2012 and tends to turn out at greater rates in midterm elections compared to the lower-propensity voters Trump gained the most with in 2024. For example, applying a simple D+5 uniform shift to the 2024 results, consistent with the latest generic ballot polling average, would already flip 4 of these 5 seats.

The story is similar when it comes to the opportunity districts, which voted for Trump by 5 to 10 points. Some of the biggest underperformers in the Republican caucus like Mariannette Miller-Meeks (D+11.3), Scott Perry (D+8.9), and Derrick Van Orden (D+7.3) represent seats in this category.

Of course, Democrats in a good year would also be expected to flip at least some, if not all, of the 9 swing seats and 4 opportunity seats held by Republican overperformers (including those who had negligible overperformances) before breaking through in any of the 27 reach seats occupied by underperformers.

The point is not to highlight all the seats where partisanship alone would give the Democrats decent to good odds of winning; rather, it is to highlight seats where partisanship and candidate quality could both favor Democrats. Mid-decade redistricting could also change the calculus for Democrats, increasing the number of competitive seats they need to flip and making candidate quality differentials all the more important as a result.

My name is Harrison Lavelle and I am a co-founder and partner at Split Ticket. I write about a variety of electoral topics and handle our Datawrapper visuals.

Contact me at @HWLavelleMaps or harrison@splitticket.org