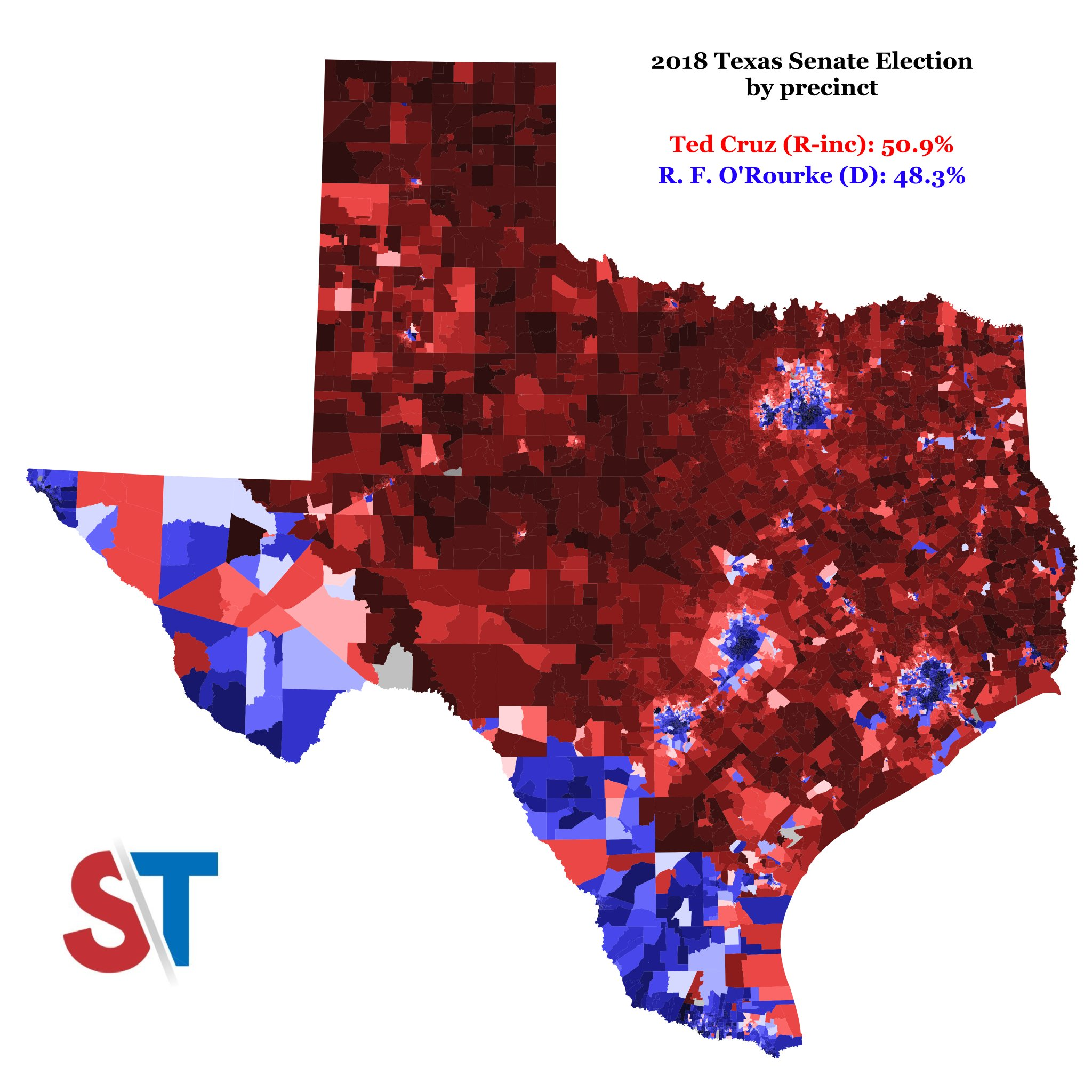

For 30 years, Texas Democrats have eagerly forecasted an eventual Democratic takeover of Texas, pinning their hopes on rapidly growing minority populations that traditionally lean blue. However, following three decades of statewide losses, observers may be excused for being skeptical of a “Blexas” future — despite the state becoming majority-minority, and despite it having shifted left a considerable amount since the Bush era, the GOP still wins it by a healthy (if weakened) margin.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle: while Texas is getting more nonwhite, and thus more demographically favorable towards Democrats, the path to a Democratic statewide win may be more complicated than relying on the archaic “demographics is destiny” tropes often repeated in electoral analysis.

A traditional rebuttal to the woes Democrats still face in Texas is the existence of an untapped voter pool, waiting to be activated. Because voter turnout among minorities is still much lower than it is among whites, the thought goes that this latent group could power them to victory in the near future (if they could only be urged to vote). But when looking at the data, this theory isn’t as open-and-shut as Democrats would hope — the Texas Democratic Party has routinely conducted mass voter registration and turnout efforts, but recent surges in registered voters have not yielded the Democratic victories (or even the gains) that activists have hoped for.

In 2018, 53.2% of eligible voters turned out to vote in Texas. Two years later, the 2020 presidential race saw a 67% statewide turnout rate. But this higher turnout saw massive Democratic collapses with traditional base demographics, particularly with Latino voters. Many of these losses stuck in 2022, where even as Republicans continued to suffer bleeding in high-turnout suburban areas, Democratic margins with Latinos hewed much more closely to 2020 numbers than to the previously higher 2018 numbers.

Given the disparate nature of the Democratic coalition, which combines lower-turnout minorities with an ascendant base of high-turnout upscale whites, this creates a picture in turnout and persuasion alike that is simply not enough to power a Democratic victory at the moment. Democrats need to make up hundreds of thousands of extra votes. But where?

The math becomes more difficult than the numbers suggest. Texas’s population is 39% Latino, according to the 2020 decennial census. When only citizen voting-age population (CVAP) is taken into account, that number drops to 31.6%. This number probably represents the maximum plausible share of Latino-eligible voters, should their registration rates climb to that of non-Latino Texans, especially given that Latino voters tend to turn out less than white voters nationally.

A map comparing 2022 CVAP to 2022 registered voters is below, illustrating that the overwhelming majority of eligible Texans are already registered. Comparing the 2022 CVAP data to the state’s registered voter data, we can see that 17.6 million of 19.2 million eligible Texan citizens over 18 are already registered, or about 92%.

Among the remaining unregistered potential voters, there doesn’t seem to be a clear, massive skew in favor of Democrats. The biggest Democratic counties of Harris (Houston), Bexar (San Antonio), Dallas, Tarrant (Fort Worth), and Travis (Austin) have roughly 650,000 unregistered per these estimates. But the rest of the state is far more red-leaning, and actually holds the balance of unregistered eligible adults, with roughly 850,000 unregistered. It is thus unclear whether registering extra voters would actually be enough to flip the state.

The next angle is turning out existing voters: those seeking to flip Texas blue usually cite the sizable Latino population, which has historically leaned Democratic, and point to their low turnout rates as the biggest obstacle keeping the state from flipping blue.

At first glance, this theory is not entirely off-base. From a demographic angle, we can observe that Latino voter registration and turnout are indeed the one group whose share of the electorate is much lower than their CVAP percentage would estimate. (Texas provides statistics on voter registration and turnout for citizens with Spanish surnames, as a proxy for Latino identity.)

While this suggests that there is a lot of room to grow for Democrats, there are a few issues with this premise. Firstly, in order to flip Texas blue by itself, all of these new unregistered Latinos would have to break nearly-unanimously for Democrats. We know from recent elections that this is not the case — Democrats win roughly 60% of Latinos statewide, and this margin among the “surge” voters would simply not be enough to flip the state on its own.

What further complicates the picture is that many of the remaining lowest-turnout Latinos are also the most Trump-curious. We see this backed up in polling, where minorities who are the least likely to vote are significantly more open to Trump than those that regularly vote. Studies done at Split Ticket also found that low-propensity Latinos are far more swingy than solidly Democratic. Thus, the notion of flipping Texas on the back of an untapped pool of Hispanic voters is simply not well-founded.

Given all of this, we can probably conclude that the statement “Texas is not a red state — it is a non-voting state” is incorrect. Under all but the most extreme turnout scenarios, it is probably fair to say that the state would still favor Republicans, especially down-ballot. However, this does not mean that the state has no avenue to flipping blue soon, especially given that Democrats have made significant persuasion-based gains in the state since Trump’s election.

But it does mean that the path to a Blue Texas may look significantly different than what has been envisioned for years. It requires a balancing act that allows the party to continue making inroads with white suburbanites without losing much ground with Trump-curious, low-propensity Latinos.

For now, however, those gains haven’t yet been enough to flip the state on their own, and a delicate balancing act is required for Democrats looking to turn the Lone Star State blue. The most electorally potent way to do this is by making continued inroads into GOP margins with educated suburban whites, while ensuring that losses with Latinos are minimized.

Perhaps the best test of whether this is feasible in 2024 will come in the Senate race, where Representative Colin Allred is seeking to unseat Senator Ted Cruz — polling shows a race with only a modest Cruz edge, and Allred has a 30% chance of an upset, per our modeling.

I’m a political analyst here at Split Ticket, where I handle the coverage of our Senate races. I graduated from Yale in 2021 with a degree in Statistics and Data Science. I’m interested in finance, education, and electoral data – and make plenty of models and maps in my free time.