Recently, a study from Stanford’s Adam Bonica came out, suggesting that moderation generally has little to do with electability, and that parties should seek to appeal to their base voters first and foremost in order to win elections.

I have a lot of respect for Adam, and I won’t cast aspersions on his work. But this finding cuts against everything we’ve modeled, and I want to show you our research in a little more detail and try to reconcile some differences between our work and the academic literature. At Split Ticket, we have modeled the last 8 years of candidate quality in congressional elections via our wins-above-replacement metric, and thus have perhaps the most comprehensive database of candidate quality in the Trump era.

Although our database covers every race contested by both parties, we’ll limit our analysis to incumbents here for ease of classification1 — while quantifying challenger ideology is quite difficult, it’s much easier to classify Congressional incumbents, as clearer ideological groupings begin to emerge in caucuses.

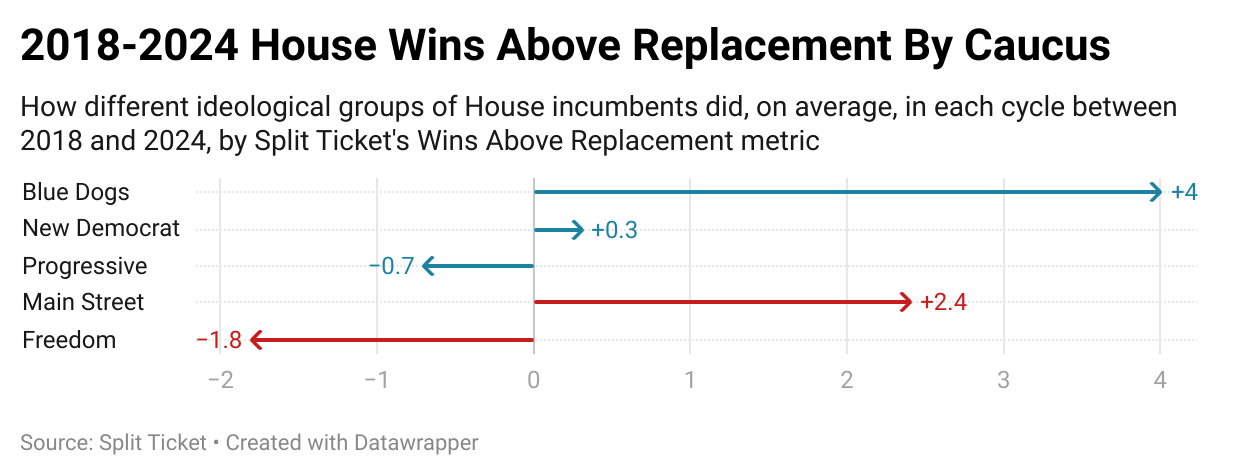

In each of the 2018, 2020, 2022, and 2024 cycles, we found that the more moderate a congressional caucus was, the better its members did, on average.

Let’s start with 2018. You can clearly see that the moderate Blue Dogs were the best Democratic caucus, doing 4.8 points better than baseline expectations, and 5 points better than the Congressional Progressive Caucus. The New Democrats, who are right in the middle of the party, did slightly better than progressives and significantly worse than the Blue Dogs.

On the Republican side, the establishment Main Street Partnership did fairly well, with its members doing 2.7 points above replacement — and it did almost 4 points better than the significantly more extreme Freedom Caucus, which is best known for its incendiary legislative tactics and hardline ideological positions.

Unsurprisingly, this dynamic was once again observed in 2020, with establishment Republicans and Blue Dogs doing tremendously well, while the Progressive and Freedom caucuses did fairly poorly. You can see some of the issues at play here — the groups most associated with Donald Trump and the more unpopular elements of the 2020 left wing ideologies did the worst, while those closer to the center did better.

Similarly, by 2022, although the playing field changed as issue salience shifted (thanks to the Dobbs v. Jackson ruling allowing for abortion bans), progressives still underperformed the New Democrats and considerably underran the Blue Dogs, even though they did better than they did in 2020. And once again, the Freedom Caucus continued to find itself on the worst ends of the electoral overperformance spectrum, doing nearly 2 percent below replacement, and 5 points worse than the establishment Main Street Republicans did.

Come 2024, you once again saw this exact same dynamic. Perhaps the only interesting thing of note was that the Main Street Republicans saw their overperformance vanish this cycle, perhaps because voters began to tie them more closely to Donald Trump. Yet the same order remained: the more moderate a caucus was, the better it did relative to the others in its party.

In other words, in every single cycle, moderation and overperformance had a direct and obvious correlation — and regardless of your thesis for the cause, the effect is clear and undeniable.

The easiest explanation for this phenomenon is that ideology really matters, and moderation generally drives overperformance. Intuitively, this makes sense: partisans are most likely to turn out and vote for their own party, while moderation usually allows you to reach and win more of the small pool of swing voters who are equally likely to vote for either party.

It doesn’t explain everything, though — critics of this theory will point out that swing voters and independents are usually the least engaged and the least likely to even know about their representatives. I believe there is also some value to this theory, but in that case, it would mean that the ideologues of each party tend to nominate people with terrible political instincts who make for worse candidates.

The truth may be a mixture of the two. But no combination is charitable towards the ideologues, and both yield the same conclusion: the more ideological lawmakers should probably not be trusted with setting the future direction of their parties. Moderates have done better in elections.

The Problem With Voting Ideology

(Warning: this segment is extremely wonky.)

Readers may note that for the analysis above, we used caucus groupings instead of voting ideology. There is a reason for this.

The most popular metric for congressional voting ideology is to use the first axis of DW-NOMINATE2 — and indeed, if you plot this against an incumbent’s WAR, you’ll find that there is basically no correlation between Democratic overperformance and moderation as measured by voting record (though it is quite sharp for Republicans). For instance, take the voting records for the 117th Congress, plotted against WAR in the 2022 midterms.

In practice, we are more skeptical of that thesis, because DW-NOMINATE’s first axis (classified as the “economic-redistributive axis”) is extremely noisy; for instance, you can see that caucuses are all over the place in voting record. The net result of this is that DW-NOMINATE implies that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is more moderate than Haley Stevens and Hakeem Jeffries. We would readily concede that if this is the metric used to gauge moderation, then moderation clearly does not have the electoral benefits we’ve claimed it does (at least, for the Democratic Party). But I would wager that virtually nobody seriously agrees with that definition of moderate.

The second axis of DW-NOMINATE, which is classified as “other votes”, is noisy, poorly understood and frequently discarded by researchers3. Some have speculated that it stands for “social views”, but in practice, it mostly seems to serve as a measure of intra-party conflict, and interestingly, it actually correlates better with electability for both parties.

This dimension is generally ignored by researchers, and for good reason: in my conversations with academics, it seems that nobody can properly make enough sense of it. But there is something interesting there, and while it’s certainly too noisy for us to confidently hang our hat on, I think it’s worth examining in future research.

The failure to create a proper and rigorously quantifiable measure of liberal, moderate and conservative should not deter us from at least making directional inferences. And for all of their issues, caucus groupings do accomplish what these measurements cannot: they provide an easier way for us to group representatives into ideological buckets to better gauge the way that they position themselves to voters. We can at least all broadly agree on their relative ideological leans: for Democrats, progressives are more liberal than New Democrats, who are more liberal than Blue Dogs. Meanwhile, for Republicans, the Freedom Caucus is certainly more conservative than the Main Street Partnership.

Because of this, we are comfortable concluding that moderates do overperform, based on the correlations observed between caucus ideology and overperformance. While our study does not establish the causality of it, the effect itself is crystal clear: moderates do better in elections.

- We have found that this tends to correlate pretty well with challenger ideology as well, at least in higher-profile cases — for instance, look at Kari Lake in Arizona, or the fact that the Blue Dog PAC consistently endorses the candidates which end up overperforming the most. But for the sake of this column, we are focusing on incumbents for ease of presentation. ↩︎

- More specifically, many now use the Nokken-Poole variant to allow for a legislator’s ideology to change over time. ↩︎

- In my conversations with academics, many of them aren’t even sure what it truly even means, in practice. ↩︎

editorial note: on June 28, 2025 and July 7, 2025, the 2018/20/22 WAR models received a minor methodological refresh to better account for district demographics and standardize methodology across cycles, due to engineering improvements made while constructing our 2016 WAR models. No major changes in caucus scores (>0.5 points) or any directional changes were observed. The figures were updated accordingly.

I’m a computer scientist who has an interest in machine learning, politics, and electoral data. I’m a cofounder and partner at Split Ticket and make many kinds of election models. I graduated from UC Berkeley and work as a software & AI engineer. You can contact me at lakshya@splitticket.org