For keen political observers, the most surprising thing about Donald Trump’s second term probably isn’t the slew of executive orders, the abrupt foreign policy pivots, or even the integration of Elon Musk in government. Instead, to many, it’s how relatively quiet Democrats have been in organizing public opposition.

There are reasons to believe that this approach is smarter than it looks. But it’s also clear that most Democratic voters are not happy with it. That’s why, two weeks ago, I mused on X that the Democrats might be at risk of their own Tea Party-esque movement in 2026. And while I don’t think that this is the most likely outcome at the moment, I think that it’s now seriously worth discussing.

I should note that I’m not claiming Democrats are poised to take 242 seats in November 2026, which is what the Tea Party carried Republicans to in 2010. The scenario I am speculating on here is one where a whole ton of established lawmakers, such as 80-year-old Dick Durbin, are forced to the exits and are replaced by younger, more outwardly-idealistic “fighters”, whether by means of retirement or primary challenges. You may call it a revolution on an age-based axis, or on a “combativeness” axis, rather than one waged on the traditional, ideological “leftist vs centrist” front.

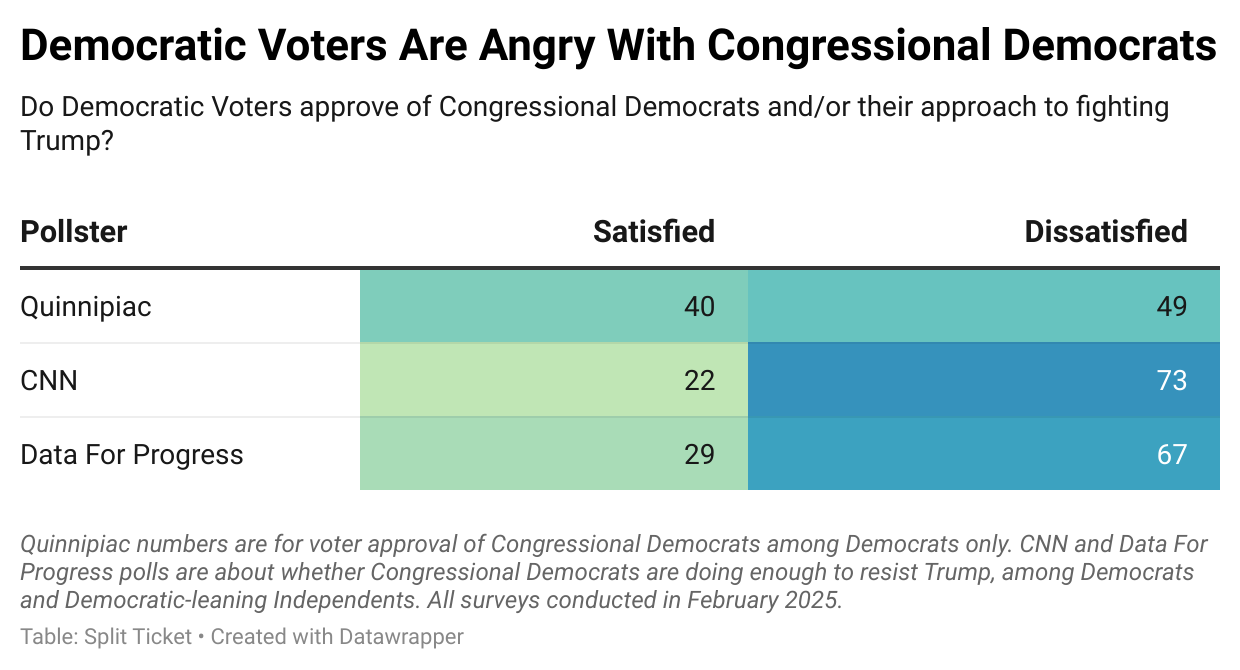

The data suggests that an insurgency is quite possible. Survey after survey shows that Democrats are extremely upset with their own party. A new Quinnipiac poll found that only 40% of Democratic voters give congressional Democrats favorable marks, compared to 49% who grade them unfavorably.

This is not simply a Quinnipiac polling artifact. A new Data For Progress poll found 67% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents wanted the party to “fight harder” against Trump, compared to just 29% who said that they were “overall doing a decent job” in resisting Trump and his administration.

To cap it all off, a new CNN poll today found 73% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents saying that the party was doing too little to oppose Trump, compared to just 22% who said they were doing the right amount.

Those are really bad numbers. Critically, this is also a relatively new phenomenon — in February 2017, Quinnipiac found that congressional Democrats had a 59% approval rating among Democratic voters. In other words, the Democratic Party’s base was far happier with the combative postures that their leaders took the last time around, and they are significantly unhappier with the more conciliatory approach this time.

To us, this is wholly unsurprising. For years, Democratic politicians have sold the public on Trump being a unique threat to democracy. Now that he’s in power, does it make sense to suddenly sit back, let him dominate the news, and “wait for him to screw up”? Regardless of the merits of the statement or the strategy, the new message is clearly at odds with what the party has done for a long time, especially as voting Democrats fear the potential long-term consequences of an unbridled Trump administration.

Given all of the above, what is the logic to their silence?

I think the simplest answer is the best one: this is the only option the leaders felt they had. There’s no 2017-esque Resistance movement to be found, and Trump began his presidency more popular than ever. The GOP caucus also enjoys a more comfortable and compliant Senate majority this time around, with Senate Republicans approving even Trump’s more controversial nominees. Moreover, instead of Democratic protests and speeches dominating social media, it’s Trump and Elon Musk on the algorithm, nearly 24/7, where the newsfeeds and replies are far more conservative now than they were eight years ago.

That’s why the Democratic Party’s leadership has adopted the new strategy of simply waiting for a blunder while letting Trump exhaust the American public, especially because they don’t actually have any real leverage (beyond lawsuits) to wield in opposition. Trump isn’t behaving in a manner consistent with the smallest popular vote victory since 2000, they argue, and this will likely lead to broad overreach and chaos that swing voters will quickly sour on.

This response is actually logical from a game theory perspective — the more a majority dominates the airwaves, the more unpopular it gets, and the more the public wants to push back. This is because Americans are generally averse to massive change, and tend to punish governmental overreach. In fact, that’s a large part of why midterms are so bad for the party in power. (Incidentally, 2022 makes a lot more sense when you view the GOP as more of the “in-power” party than the usual “out-party” for overturning abortion, which upended the lives of swing-state residents far more than any Biden policy did).

Dominating the airwaves with symbolic protests, Democratic leaders argue, would do little to actually block him or Musk compared to the (often successful) lawsuits that Democrats are peppering federal courts with. Instead, it would only serve to re-polarize the electorate pre-emptively, capping the gains that Democrats could get with swing voters and facilitating Trump’s attempts at turning policy into political theater.

There are signs this approach is working — as Trump and Musk continue to make news, the President’s approval is rapidly decreasing and is now almost back to neutral, as per FiveThirtyEight’s tracker, which is down from the +8 he began his term with. And as a public opinion and polling nerd, I think this approach actually has the potential to create larger and more lasting gains, so I’m more understanding of it.

What I also think is true, however, is that most Democratic voters are not okay with this approach. And right now, there are simply too many people that hate both Donald Trump and the Democratic Party for this equilibrium to remain.

It’s important to remember, again, that unlike the Tea Party of 2010, this is not an issue that breaks down cleanly along ideological lines. An insurgency isn’t necessarily going to pull Democrats to the left, especially because Democratic voters can’t really agree on which ideological direction to take their party. (In recent Gallup polling, 45% wanted the party to become more moderate, 29% wanted it to become more liberal, and 22% were fine with its current ideology.)

But ideology isn’t the only thing that elections are fought over. And dissatisfaction is so widespread with the party’s leadership’s approach to Trump that I think something is going to give, and potentially soon. Whether it’s the strategy that changes or the lawmakers themselves, though, is yet to be determined, especially with over a year to go until the midterm cycle begins in earnest.

I’m a computer scientist who has an interest in machine learning, politics, and electoral data. I’m a cofounder and partner at Split Ticket and make many kinds of election models. I graduated from UC Berkeley and work as a software & AI engineer. You can contact me at lakshya@splitticket.org