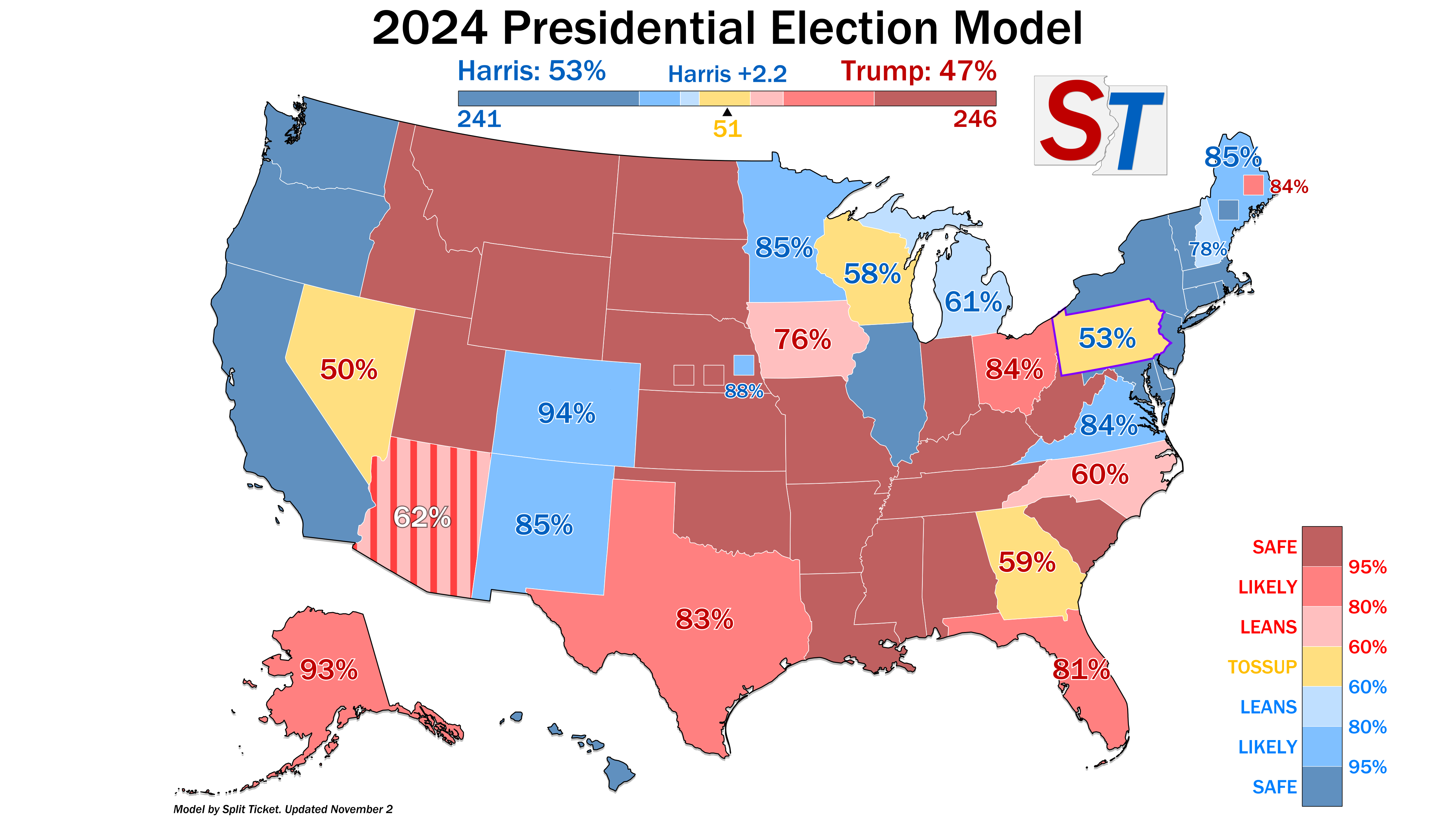

With just three days to go until election day, our forecast remains that the presidency is a pure tossup, with Kamala Harris at a 53% chance to win and Donald Trump at a 47% chance to win. Harris is a nominal favorite, and so if you forced us to make a pick for the presidency, we’d have to go with her. But it’s extremely easy to see either Trump or Harris pulling out the win come November, based on the data available to us.

So instead of giving you a standard forecast recap that we’d simply repeat in two days for our final preview, we think it would be more informative if we made the case for each candidate’s victory, to prepare you for how things might go (along with a section talking about that Selzer poll at the end).

The Case for Donald Trump

There has always been a lot to like about Trump’s position. Let’s zoom out, for a moment, and examine a hypothetical country under similar circumstances.

In this country, the incumbent government is quite unpopular, having been especially damaged by cumulated effects of inflation and post-pandemic economic instability. This is hardly unusual. In fact, it is quite common. Over the past several years, many incumbent governments have grown incredibly unpopular, and have lost by landslide margins to oppositions advocating for change — on all sides of the political spectrum.

Our hypothetical country is no different. In an effort to mitigate some of the damage, the incumbent party has replaced their unpopular leader seeking reelection, which has boosted them in the polls but does not free them from baggage of the past several years. Heading the opposition is a former government leader, who was narrowly ousted in the last election. While this leader has baggage of their own, they are generally seen as stronger on the issues rated most important by voters in the polls (such as the economy or immigration). Critically, they are also viewed as less ideologically extreme than the incumbent party’s leader.

Under these circumstances, you may be surprised to learn that the opposition is not, actually, leading in the polls, despite a litany of factors that lean in their favor. This, essentially, is where Trump stands now. The underlying dynamics of this election, such as Biden’s unpopularity and mass dissatisfaction with the direction of the country and the economy, have not changed even with the Harris swap-out. One of the more remarkable things about this election is just how little they appear to be weighing on the Democratic Party as a whole, but that still leaves Harris in a complete toss-up race.

Unlike 2016 and 2020, Trump does not need a significant polling error to win this election. Indeed, polls could be historically accurate and still lead to a Trump victory, perhaps one where he sweeps both the Sun Belt and Rust Belt. As of November 2nd, our polling averages have Trump trailing by 0.5% in the likeliest tipping point state, Pennsylvania. It should not surprise anybody if he were to win here, or in any of the seven core swing states.

It is, of course, possible that Trump will yet again outperform his polls, potentially by a significant margin (although this is also true of Kamala Harris). This may be the case for a variety of reasons, such as pollsters still being unable to accurately capture Trump’s support with low turnout, less engaged voters who are unlikely to answer polls. If that occurs, Trump is extremely well-positioned.

Although Trump has a long list of glaring weaknesses, such as his felony convictions, his ties to the end of Roe v. Wade, and his efforts to overturn the 2020 election, his overall favorability ratings have not taken a fatal hit. Quite the contrary, in fact, as some polls (such as NYT/Siena) have found his favorability close to even. Voters also view his presidency in a positive light, as he appears to have escaped blame for much of what happened during 2020.

The other, simple truth: Harris cannot afford to lose much, if any, ground relative to Biden’s performance in 2020. Biden’s win in the Electoral College was built on margins of less than a percentage point in Georgia, Arizona, and Wisconsin. His victories in Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Michigan ranged between 1 to 3 points. In order to win again, Harris needs to reassemble as much of Biden’s coalition as possible; even small defections could cost her dearly.

Trump, however, does appear to have bitten into the Biden coalition, particularly among young, nonwhite voters who were previously overwhelmingly Democratic. There are many skeptics of another Trump-induced realignment of nonwhites toward the Republican Party, but it is worth noting he does not need a huge realignment to flip states like Georgia; even modest gains with Black voters, for example, may be sufficient there.

These gains have narrowed the Democratic margin in national polling. Biden won the national popular vote by 4.5 percentage points, but Harris leads by just 1.5 points in our averages. A universal 3-point shift across all 50 states would amount to a relatively mild change nationwide, but would ensure a Trump victory. Harris’ chances are kept afloat by the fact that Trump appears to have gained the most with demographics concentrated in safe states, and the least with northern whites, who are heavily overrepresented in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

To put it simply, through luck, skill, or a combination of both, Trump has a favorable hand. His position is not that different from where he was in 2020, when he narrowly lost the election; in some ways, it is even better. As it happens, his opponent may be skilled enough to outplay him, or his own tactical errors could very well cost him the race. But by this time next week, it may be easy to see how a Trump victory was in the cards all along.

The Case For Kamala Harris

If you’re of the thought that Kamala Harris will win, you’d be excused for being bewildered by the prediction market swings over the last few weeks. The bearishness on her comes from three main angles: the previous cycles’ under-estimation of Trump, the recent tightening in national surveys, and the early vote.

But the fundamentals look quite good for Harris, at least compared to polling. The most significant of these is Washington’s top-two, nonpartisan “blanket primary”, which actually points to a result around D +3–4 nationally. Moreover, the non-urban part of the state, which cratered for Democrats in 2016 and showed surprisingly weak results in 2020, now shows a swing to the left in 2024, as Democrats gain with secular and non-college white voters.

In 2016, 2018, and 2020, the results in Washington portended the Democratic struggles in the Midwest, and they warned of a race that was nowhere near as blue as surveys implied. This time around, however, they suggest that the party may be in better shape there than the polling might suggest. While they don’t indicate a blue wave, they do point to the party holding the demographically-similar Blue Wall states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

We’ve also seen the early vote analysis people have peddled, and we’ve extensively detailed our skepticism regarding them. We’ve already given examples of why applying 2020 splits by vote method (mail, early in-person, and election day) is an incredibly poor method of analysis, and we’ve also highlighted that election day is set to be a lot bluer than it was in 2020 and likely even 2022, as Democrats are simply returning their ballots later.

Most of the GOP strength in early voting is simply because a non-trivial chunk of their 2020 election day voters are now voting early, as Trump and the GOP embrace early voting. In North Carolina, 40% of the registered Republicans who voted on election day in 2020 have now voted early, while just 20% of Democrats have. In Nevada’s Clark County, this number is 33% for Republicans, while it’s just 15% for Democrats. And in Georgia, which has no party registration but is heavily polarized by race, roughly 33% of white voters who voted on election day in 2020 have voted early; however, for Black voters, this number is just 20%.

There are two ways to reconcile this reality. The first is to suggest that Democrats are simply going to vote later, and that election day will be substantially bluer (and less white) than it was in 2020. This would track with the return patterns we are seeing and the statistics cited above. You can see an example of this in a chart assembled for us by Daniel Sokul, who has tracked Harris County’s returns in Texas. Democrats are returning their ballots far later than they were in 2020, and as the election nears, their voting rate has dramatically picked up (a stark reversal from 2020).

If delayed Democratic turnout does not materialize, the only possibility is that Republicans are going to enjoy a landslide turnout advantage, with Democrats essentially boycotting the election en masse. Given the incredibly poor track record that unqualified early voting analysis tends to have, we lean towards the first theory — in a presidential cycle, both parties will likely show up, and any turnout advantage the Republicans have will likely be marginal at best in most states, though it reduces the turnout the GOP will need on Tuesday.

Finally, the majority of skepticism and pushback on Harris that we receive comes from people burned from previous polling misses. To this, we’d point out that polls rarely continue to miss in the same direction, because pollsters adjust for what they missed the last time around. We have no evidence to suggest that polls are set to underestimate Trump once more.

To begin with, we have strong evidence that the response environments this time are simply different. In 2016, we now know that a primary driver of polls missing on Trump was due to not weighting on certain factors, such as education, that had become dividing lines in American politics. In 2020, the cause of the miss was different — polls were simply far more likely to reach Democratic-leaning voters, who were staying home amidst COVID and were thus more likely to respond.

Looking at the response environments, we can see more evidence of the underlying shift in reality. Take a look at YouGov’s data and you can see that Democrats have become significantly less likely to respond to polls over the course of the cycle, which is extremely different from how polling worked in 2016 and 2020 (and even immediately post-Dobbs in 2022). For the first presidential cycle in a while, pollsters are actually getting a pretty good balance of Democrats and Republicans in their raw samples, even before stratifying and weighting their electorates.

There are real reputational and psychological costs to repeatedly making these types of mistakes, and we can observe that pollsters have taken a lot of steps to ensure they get enough Trump supporters this time around (as they did in 2022). Whether through weighting by recalled vote (which explicitly tries to get a set number of self-identified Trump supporters in a survey), through more GOP-friendly likely voter screens, or other methodological choices, it is clear that something has changed.

As a last point, there are a shade too many tied polls in Pennsylvania (at least, compared to what would mathematically be possible, even after accounting for how variance shrinks when you weight surveys on common factors). If this is true, then the aggregate will likely miss by more than it has in the past. We have no way to know which direction this error cuts in, but it is probably worth noting that registered voter polls in Pennsylvania consistently find Harris up, even as likely voter (LV) polls find her down, and that there is a curious discrepancy between national and statewide LV polls.

Then, there’s the whole matter of outliers and that Selzer poll. And while it’s just one poll, it’s perhaps one of the only ones worth its weight in gold, as Selzer’s outliers have consistently been more correct than the results of the industry as a whole, over the course of a full decade.

So, About That Selzer Poll.

Do you get deja vu?

Four years ago, the race in Iowa was looking extremely tight. FiveThirtyEight’s polling average actually had Joe Biden practically tied with Trump in the Hawkeye State. At the time, this hardly seemed unusual; polls consistently said Biden was poised to make a big recovery with the Midwestern working class whites who had abandoned Hillary Clinton, and Iowa was the epicenter of that shift. The Selzer poll from September had found both candidates tied, 47–47, reinforcing this belief.

Then, Selzer dropped a bomb in the final week, with a survey that showed Trump ahead 48–41. This was a finding that suggested Trump was actually well-positioned to replicate his 2016 performance in Iowa, with big implications for the rest of the Midwest. It was Trump’s best poll in months, and arguably his best one of the entire year. And at the end of the day, Selzer turned out to be right, just as she was in the 2008 Democratic caucuses, in the 2014 Senate election, and the 2016 election — her outlier polls, once again, continued to consistently catch something that no other pollster was seeing.

This was, however, a huge deviation from basically every other poll of the cycle, and came with a number of caveats. Selzer is one of the most respected pollsters in the country, but no pollster is free from the laws of the universe that govern statistics. Sampling error is always a possibility, and her polls, even with their phenomenal track record, are not infrequently off by a point or two. And, of course, it was just one poll — the data in aggregate said something different.

All of these caveats apply to the astonishing poll that Selzer released this evening, where Kamala Harris leads Donald Trump, 47–44, in Iowa. It is inarguably one of the best results for Harris of the cycle. Although Iowa polling has been sparse (neither candidate is treating it as a swing state, given Trump’s 8-point margin there in 2020), there is scant evidence anywhere of the surge in support Harris would need to flip Iowa.

Nevertheless, Selzer’s track record is close to immaculate, and consequently her polls are given substantial weight in our model. The model is ultimately skeptical of this result, which goes against almost the entirety of the available data. Just today, for example, Emerson College found Trump ahead 53-43 in Iowa. Still, this poll alone moves Iowa to Leans Republican in our forecast, with Trump being a 76% favorite to keep the state in his column — a marked decline from the 88% chance the forecast gave him just yesterday.

If this poll is anywhere near correct, the implications are vast. It is difficult to imagine a universe in which Kamala Harris achieves the level of white support necessary to be competitive in Iowa, but does not win Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Nebraska’s second congressional district – and with it, the election.

While no other poll has shown quite this monumental of a shift, if you squint, there are perhaps hints of something similar happening in polls of similar states. Harris has polled exceptionally well in Nebraska’s second congressional district, and some polls of Nebraska statewide show a shift toward her as well. There was also a recent poll of Kansas that only had Trump up 48-43, a seeming outlier, but one perhaps worth taking a second look at in the wake of this poll.

Does this poll imply a Harris landslide? That’s one interpretation we’re skeptical of — even setting aside the outlier nature of this poll, it is worth noting that even a perfectly accurate Iowa poll cannot say much about states like Georgia or Arizona, where the whites vote differently from the Midwest. Barack Obama, for example, won Iowa easily en route to losing both of those states, and the idea of Harris possibly replicating something closer to the Obama coalition seems far-fetched. (But, then again, so does the idea of Harris being competitive in Iowa at all).

We have criticized pollster “herding,” a dynamic in which polls crowd around the expected result, instead of being willing to publish outliers or other surprising results. One thing is clear: Ann Selzer is not herding. It is possible that this becomes the first Selzer poll to seriously miss, through no fault of its own — again, sampling error can be unavoidable. On the other hand, perhaps Selzer is once again correct, and pollsters have been seriously underestimating Harris, an outcome that would remind people, at the very least, that polling error is unpredictable.

In three days, we will have our answer.

Addendum: A big thanks to Daniel Sokul for his help with gathering early voting data for this article.

I am an analyst specializing in elections and demography, as well as a student studying political science, sociology, and data science at Vanderbilt University. I use election data to make maps and graphics. In my spare time, you can usually find me somewhere on the Chesapeake Bay. You can find me at @maxtmcc on Twitter.

I’m a computer scientist who has an interest in machine learning, politics, and electoral data. I’m a cofounder and partner at Split Ticket and make many kinds of election models. I graduated from UC Berkeley and work as a software & AI engineer. You can contact me at lakshya@splitticket.org