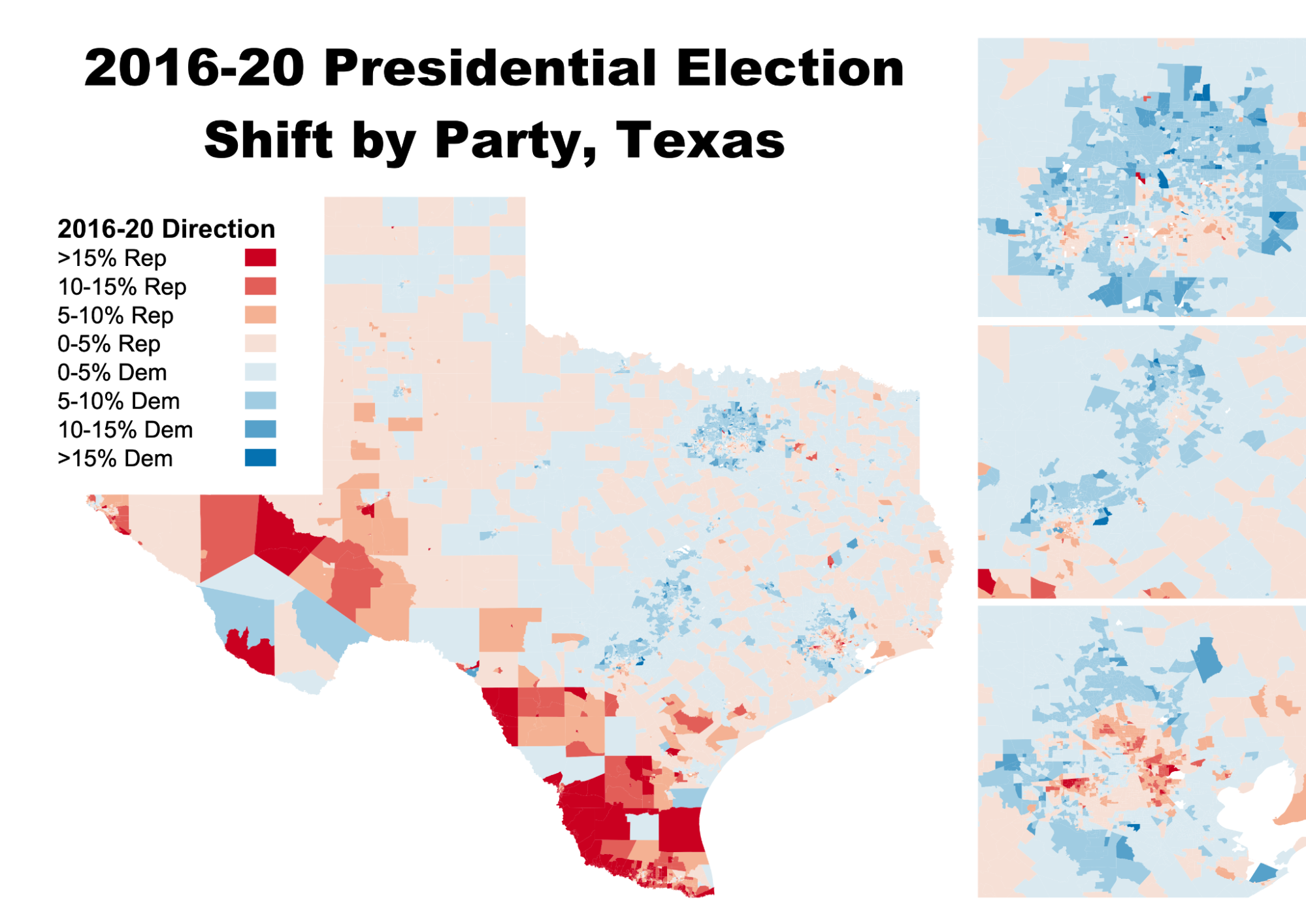

In the 2020 presidential election, one of the largest political shifts occurred in Latino communities. While Democrats still won Latino communities by-and-large, more Latinos from Florida to California voted for Trump in 2020 than in 2016. Perhaps the most eye-grabbing rightward shift came from the Texan border with Mexico, especially in the rural counties near the Rio Grande Valley (RGV). Margins in some counties swung as much as 50% towards Trump, perplexing many observers after years of what many consider anti-Latino rhetoric and policies from the incumbent president.

While the national Latino rightward shift was much smaller (estimates range from 2–10%), these rightward trends in this large and growing voting bloc could restructure American politics if it continues. Consequently, political scientists, strategists, and journalists have tried to explain this Latino shift towards Trump in 2020.

Some of these explanations revolve around the conservative social, racial, and cultural aspects of Latino communities. Latinos, according to these theories, skew ideologically moderate and are moving away from an increasingly-liberal Democratic Party.

However, the same year Latinos shifted to Trump, they had also voted for Democratic Socialist Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders in the Democratic presidential primaries.

Sanders both vastly improved on his 2016 performance and outright won most Latino communities across the early primary states when the race for the Democratic Party nomination was competitive — especially in heavily-Latino areas of Texas.

Sanders’ success in 2020 disputes the theory that Latinos shifted right solely because they’re socially conservative and ideologically moderate. Sanders is socially liberal and is ideologically neither moderate nor similar to the former President.

To complete the story of this political shift, I delved deeper into Texas precinct-level election results and built a population-weighted regression model to find statistical patterns that predicted a partisan shift in 2020 across the state. Specifically, I tested race, income, college education, county population density, and age as potential predictors of both Trump gains between 2016–2020 and Bernie Sanders’ 2016–2020 gains in Democratic primary vote share.

Controlling for all the aforementioned variables gave an R-squared value of 0.46 and showed the strongest predictor of Trump gains from 2016–2020 was indeed Sanders gains in the same timespan. Latino share of the population was only the second-greatest predictor. Incidentally, an interaction term multiplying both variables together is even more predictive, meaning the two are interconnected and best at predicting Trump gains together — which is discussed in further here.

Mapping election results out confirms that it was the same Latino precincts that shifted towards Sanders that shifted towards Trump — and these majority-Latino precincts represent both the lion’s share of Latinos and of the precincts that shifted toward Trump.

This is not the first time parallels have been drawn between Sanders and Trump. Both candidates were political outsiders in 2016 and ran on economic populist platforms. In 2016, Sanders and Trump both excelled in white, rural white working class in places like Michigan and West Virginia, which was attributed to their similarly populist messages. What we saw in Texas in 2020 suggests that this Sanders-Trump populist parallel extends beyond the white working class, and to the nonwhite working class as well.

Under this framework, the Latino rightward shift in 2020 might be better explained by socioeconomic factors. Latinos (especially in rural, south Texas) are disproportionately working class, making them receptive to populist economic messages. These populist shifts were larger in poorer, rural Latino precincts with lower education attainment rates than urban ones, further suggesting class and education are catalysts for gains by Trump (and Sanders). This is not merely speculation; LULAC leader Domingo Garcia explicitly named economic populism as a strategy necessary to win Latino voters, and this is confirmed in the data: studies by polling firm Equis suggest that economic issues were front and center among Latino voters in 2020.

While it’s true Democratic primary voters are not representative of all general election voters, the sheer correlational strength suggests there is at least some relationship between Trump’s success in Latino communities with economic populism. Additionally, because most Latinos identify as Democrats (44–25%), heavily-Latino areas have much more overlap between their Democratic primary and general electorates. Even if it was not pro-Sanders Latino Democrats who shifted towards Trump, it was their neighbors and family members. These voters live in the same communities and face the same economic realities, and were subsequently attracted to both economically populist candidates.

Looking ahead to 2024, a campaign which wishes to be successful among these voters must have a strong, populist economic plank. Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign appears to be starting to do just that. Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson notes that Harris could be climbing in the polls because she is regaining trust that President Joe Biden lost on handling the economy while simultaneously reviving Latino support that Biden had lost.

Beyond the 2024 election, the growing “nonwhite populism” could transform American partisan politics. If Democrats want to contest increasingly-Latino Texas, they should consider Sanders’ success in Latino areas when forming their economic legislative agenda and electoral platform. If someone seen as racially inflammatory as Trump can win record vote shares along the Mexican border, a Democratic Party seen as weak on working class economic issues could slow or even reverse Democrats’ ascent in Texas and flip the RGV’s 3 congressional districts — and swing Latino communities beyond Texas.

Finally, 2020 Texas Latinos show that the supposed “racial realignment” of Latinos and other nonwhites shifting to the Republicans may actually be an extension of a class realignment: working class voters — white, Latino, and others — are becoming Republicans while college-educated voters are switching to Democrats. Because Latinos are disproportionately working class, a working class shift can manifest as a Latino shift. But this can convolute the fact that many college-educated people of color are not moving right in the same way, like in the diverse suburbs of Atlanta, Houston, and Northern Virginia.

Data Sources

- Redistricting Data Hub

- US Census Bureau

- Texas Secretary of State Election Results

- Data modelling specifics, produced by Andrew Hong, can be reviewed here.

Andrew Hong

I’m a guest contributor at Split Ticket, separate from my 9-5 as a political data analyst at HaystaqDNA and WA Community Alliance. I study data science and computational social science at Stanford University. Seattle is home.

I make election maps! If you’re reading a Split Ticket article, then odds are you’ve seen one of them. I’m an engineering student at UCLA and electoral politics are a great way for me to exercise creativity away from schoolwork. I also run and love the outdoors!

You can contact me @politicsmaps on Twitter.