Last month, the Cook Political Report published an article with some eye-opening statistics: over their 38-year history, more than 95% of races they called as “leaning” toward a party went to said party. By contrast, over 97% of races they called as “likely” to go to a party resolved as such — a mere 2% difference in probability.

These statistics were framed as a massive accomplishment, and certainly speaks to their credibility when calling a favorite in a race. But it also begs the question: what do their ratings actually mean? What do any of the expert forecasters’ ratings actually mean? Obviously, a rating with a 95% accuracy rate cannot mean a race merely “leans” toward a candidate, and in fact must exclude many races with that level of uncertainty.

This is just one of the many nuances that contextualize the experts’ forecasts. Forecasts that are informative, yet incredibly cautious, in ways that give weight to their calls, but create a strong bias toward uncertainty. For organizations with a reputation at stake, this caution is intentional. It is certainly more responsible, at least, than faulting toward recklessness.

Still, after exploring the statistics below, one starts to wonder if maybe, just maybe, the experts could stand to be a bit more nimble.

METHODOLOGY

For the sake of comparison, this article will review the three largest forecasters that use the standard Tossup/Lean/Likely rating schema: the Cook Political Report, Sabato’s Crystal Ball, and FiveThirtyEight (538). For the following section, the ratings reviewed will only include the November general elections in 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022, and will exclude races that went to a runoff, as well as the invalidated 2018 NC-09 House election.

WHAT DOES A RATING MEAN?

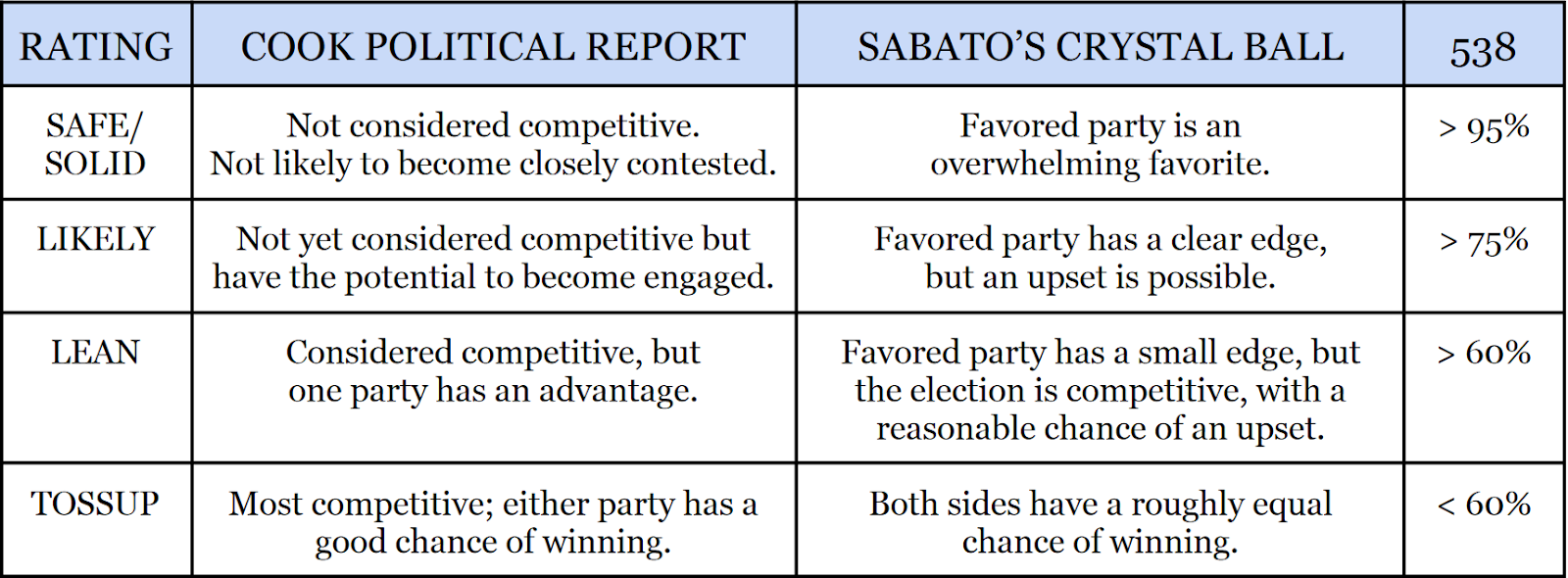

First things first, what does each rating mean? While a seemingly basic question with intuitive answers, it is a lot more important than one might think. Given the lack of standardized definitions, different forecasters have actually adopted significantly differing interpretations for each category.

At first glance, these definitions may seem roughly equivalent. However, when you look at the accuracy rates below, the definitional differences become a lot easier to see.

When the Cook Political Report declares that a race is “competitive, but one party has an advantage”, at least in their final ratings, what they really mean is “we are very confident this party will win this race. If we weren’t, we would’ve rated it as a Tossup.” Likewise, while the word “tossup” connotes a coin flip, where both sides have similar chances of winning, Cook instead defines it to mean races “either party has a good chance of winning.” As mentioned in the introduction, the absurdly-high accuracy of Cook’s Lean ratings implies that their Tossup races include those where one side does have an advantage, but not one insurmountable enough to make their Lean category.

To be clear, this is a reasonable choice for an organization to make – prioritizing accuracy above all else. However, it’s a choice that deviates from the common meaning of their terminology.

By contrast, the forecasters at Sabato’s Crystal Ball employ a very different definition of “Lean” — specifically meaning a “small edge” — and it shows in their lower, yet still formidable 77% accuracy rate for the category. However, this comes with a massive caveat: for their final ratings, the Crystal Ball generally always chooses a side — taking the opposite approach of Cook.

This begs the question: which approach is more “correct”? Is Cook correct that they truly could not accurately pick favorites among their Tossups? Is the Crystal Ball being reckless in doing so anyway? To answer this, the chart below displays the Crystal Ball’s accuracy in picking favorites among Cook’s Tossups.

Fittingly, the results of this analysis could go either way. While the Crystal Ball has more often than not picked favorites correctly, demonstrating their psephological skill, it was not overwhelmingly so. For instance, in 2022, the Crystal Ball only rated half of Cook’s Tossups correctly. This is balanced out by years like 2018, where the Crystal Ball rated a stellar 78% of Cook’s Tossups correctly. In other words, the Crystal Ball has called more races correctly than Cook, but has also called more races incorrectly (by a smaller amount). As such, it is up to the reader’s interpretation the correctness of each organization’s approach.

Finally, there’s FiveThirtyEight, who differs from the aforementioned forecasters in two crucial ways. First, while human forecasters judge and pick ratings within Cook and Crystal Ball, 538’s ratings are produced exclusively by machines running their probabilistic forecasting models. Second, 538’s rating definitions are much looser than Cook’s or the Crystal Ball’s. For instance, any race with a 95% chance or higher of going to the other party is rated as “Solid” for that party by 538 (for reference, that’s nearly Cook’s standard for their Lean category). This has resulted in 538 incorrectly rating two Solid races over the last four cycles (2018 OK-05, 2022 WA-03). By contrast, the Crystal Ball’s only incorrect Safe call during this time was the 2022 special election for AK-AL, while Cook nearly had their first Solid miss in fourteen years with the 554-vote squeaker in 2022 CO-03.

In general, 538’s looser definitions have led them to rate races more strongly than their counterparts, rating ~40% less races as Lean or Tossup than either Cook or Crystal Ball, and ~20% less races as unsafe overall. Despite this, 538 still wields an impressive 78% accuracy rate for their Lean ratings (greater than the 60%–75% accuracy they’re designed to have), as well as a 92% accuracy rate for their Likely ratings.

As a data-driven website, FiveThirtyEight caters to an audience that (it hopes) will understand that events with a 5% chance of happening should happen one in twenty times. However, for outlets like Cook or Crystal Ball, with perhaps a less wonky group of readers, it seems miscalling a Safe race is avoided at nearly every cost. As such, while the median “Likely” race according to 538 was won by ~8%, more than half of the races Cook or Crystal Ball deemed “Likely” were won by double digits. In other words, Cook and Crystal Ball are rating as “Likely” many races that seem rather “Safe” for a party, likely to cover the tail-end possibility that the seats go the other way.

LAGGING INDICATORS

While the previous section focused on the forecasters’ final ratings, the side effects of their caution do not end there.

To quote from FiveThirtyEight’s old model methodology:

“…although the expert raters are really quite outstanding at identifying ‘micro’ conditions on the ground, including factors that might otherwise be hard to measure, they tend to be lagging indicators of the macro political environment. Several of the expert raters shifted their projections sharply toward the Democrats in early 2018, for instance, even though the generic ballot was fairly steady over that period.”

This phenomenon has been replicated multiple times since. In 2020, Biden held a large and steady polling lead onwards from March, yet neither Cook nor the Crystal Ball made updates to reflect this until late June/early July. In 2022, the GOP started consistently leading the generic ballot in January, yet neither forecaster shifted their ratings decisively redder until late April.

This is no accident. Polling is prone to short-term blips, so one must wait to judge the staying power of any shift. The forecasters do seem to move in tandem, though, when declaring a shift in the political environment. For instance, on July 14, 2020, the Crystal Ball moved seven safely Republican states into Likely R to account for a possible Biden landslide. That same day, Cook moved four of the seven to Likely R, and they moved the rest ten days later.

The existence of these tandem moves, untriggered by any immediate event, has a few possible explanations. The simplest is that there does exist a shared event that the public isn’t aware of. For example, on October 19, 2022, both Cook and the Crystal Ball moved MT-01, a red Trump+7 district, from Likely R to Lean R. While there was no obvious trigger for this change, it is likely that both forecasters had recently been tipped internal data showing a surprisingly competitive race. That said, this explanation is unlikely to apply when rating shifts reflect a broad change in political environment.

An alternative explanation, drawn through private conversations and public comments, is this: when bolder calls are to be made, tandem moves can dampen the backlash. Bold calls inevitably draw criticism, and this is doubly so for calls as impactful as environment shifts. Forecasters are not immune to public pressure, and when one forecaster decides a fundamentals update is long past due, it creates an opportunity for others to swiftly follow in turn. However, until such an opportunity arises, the forecasts will usually lag a few months behind the macro data.

This is a key advantage of FiveThirtyEight’s models. Flawed as they may sometimes be, the machine is immune to public pressure, and reacts immediately to the newest data. It’s worth noting, however, that FiveThirtyEight’s models come online later in an election cycle, when polling is more plentiful, and forecasters seem less hesitant to make large scale shifts.

Conclusions

The purpose of this piece is not to bash the big forecasters — as seen in the charts above, their accuracy is quite superb. Nevertheless, experts have received unduly vicious criticism for “missing” Trump’s 2016 election, Biden’s narrow 2020 victory, and 2022’s red ripple midterm. Thus, despite their stellar prediction records, it would not be surprising for them to act more cautiously than ever.

In the end, all conclusions are the reader’s to make. As the forecasts are clouded by caution and uncertainty, hopefully readers can now better interpret what the experts wish to say.

Just another election data guy from New Jersey. Proudly competent at predicting the midterms. You can find me tracking special elections and other election-related data/nonsense on Twitter at @ECaliberSeven.